Image/Shutterstock.com

By Angharad Brewer Gillham, Frontiers Science Writer

‘Social loafing’ is a phenomenon that occurs when team members put forth less effort because they know others will do it for them. Scientists who investigated whether this happens in teams that combine robot and human work found that humans performing quality assurance tasks detected fewer errors when they were told that the robot had already checked the part. work.

Advances in technology have now led some robots to work alongside humans, there is evidence that humans have learned to see robots as teammates, and teamwork can have negative as well as positive effects on human performance. People sometimes let their colleagues do the work for them and relax. This is called ‘social loafing’ and is common when people know their contribution will not go unnoticed or adapt to the high performance of other team members. Scientists at the Technical University of Berlin investigated whether humans become socially lazy when working with robots.

“Teamwork is a mixed blessing,” said Dietlind Helene Cymek, first author of the study. Frontiers in robotics and AI. “Working together can motivate people to perform well, but it can also lead to a loss of motivation because individual contributions go unnoticed. “I was interested to see whether this motivational effect could be found even when the team partner was a robot.”

helping hand

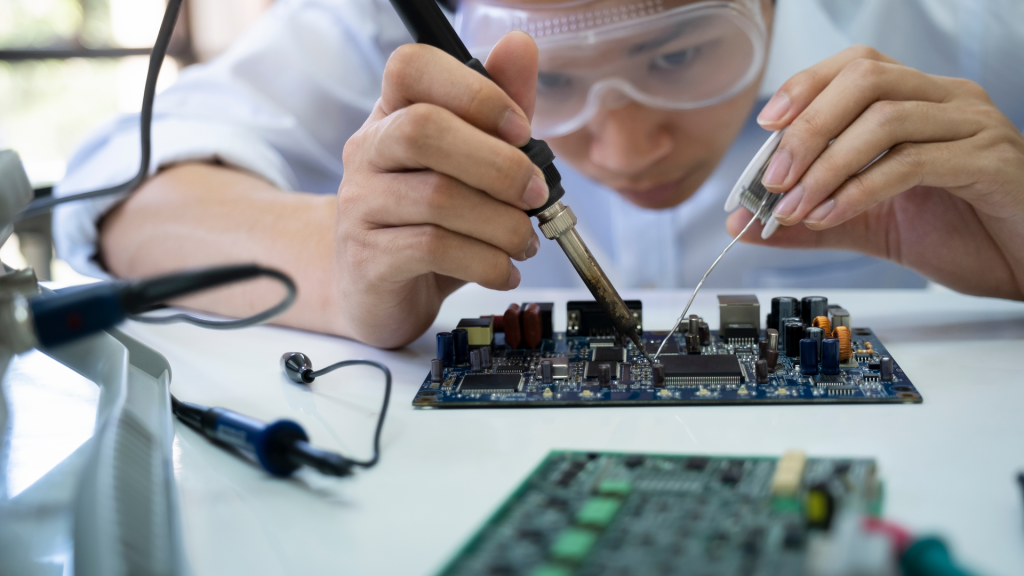

The scientists tested their hypothesis using a simulated industrial defect inspection task (checking for errors in circuit boards). Scientists provided images of circuit boards to 42 participants. The circuit board was blurry, and I had to hover my mouse over it to see a clear image. This allowed scientists to track participants’ board examinations.

Half of the participants were told that they were working on a circuit board that was inspected by a robot called Panda. Although these participants did not work directly with Panda, they could see and hear the robot while they worked. After inspecting and marking the board for errors, all participants were asked to rate their effort, responsibility for the task, and performance.

Looking but not seeing

At first glance, the panda’s presence seemed to make no difference. There were no statistically significant differences between groups in the time spent examining the circuit board and the area searched. Participants in both groups rated their task responsibility, effort, and performance similarly.

But when the scientists looked more closely at the participants’ error rates, they realized that participants who worked with Panda noticed fewer defects later in the task, even though Panda had already successfully flagged many errors. This may reflect the ‘see but don’t see’ effect, where people become accustomed to relying on something and become less mentally involved. Although participants thought they were paying just as much attention, they subconsciously assumed that the panda hadn’t missed any defects.

“It’s easy to keep track of where a person is looking, but it’s much more difficult to determine whether visual information is being sufficiently processed at a mental level,” said Linda Onnasch, Ph.D., lead author of the study.

Experimental setup of human-robot team. Image provided by author.

Is your safety at risk?

The authors warned that this could have safety implications. “In our experiments, subjects performed the task for about 90 minutes, and we have already discovered that there are fewer quality errors found when working in teams,” Onnasch said. “In long shifts, the loss of motivation tends to be much greater when tasks are routine and the work environment provides little performance monitoring and feedback. “In manufacturing in general, and especially in safety-related areas where double checking is common, this can have a negative impact on work results.”

The scientists noted that their test had several limitations. Participants were teamed up with a robot and demonstrated the robot’s work, but did not work directly with Panda. Additionally, social loafing is difficult to simulate in the laboratory because participants know they are being watched.

“The biggest limitation is the laboratory environment,” explains Cymek. “To find out how big the problem of loss of motivation is in human-robot interactions, we need to go into the field and test our assumptions in real-world work environments with skilled workers who routinely work in teams with robots.”

Frontier Journals and Blogs