Martin Chandler |

Years ago, I used to regularly profile great athletes. Sometimes there were players who weren’t that great. I haven’t done much of it in a while because I think I’ve decided, even if not consciously, to read other people’s work rather than create my own. Or is it a lack of topics of interest?

One name that always appealed to me was the name Rony Stanyforth. I knew that Stanyforth had captained England to South Africa in 1927/28 despite never being a regular for his county, Yorkshire, but I knew little more about him. The appeal grew out of a discussion with a tragic colleague about who the least-known England captain is.

In fact, I think that title should go to Monty Bowden, who, at the age of 23, led England against South Africa at Newlands in the second of the two Tests in 1888/89. Bowden, a humble batsman and occasional wicket-keeper, remained in South Africa until the end of the tour and died three years later, but unlike Stanyforth he is the subject of a biography, although he is not often seen*.

But since I doubt anyone would dispute the claim that Stanyforth is Britain’s most obscure 20th century captain, I decided to look into his story. Given the relative paucity of first-class cricket featuring Stanyforth, I certainly found the story interesting, but its length was closer to 3,000 words, which for some reason now unknown to me, I always regarded as the ideal length for a profile. , so I shelved the idea and the story stayed on my hard drive.

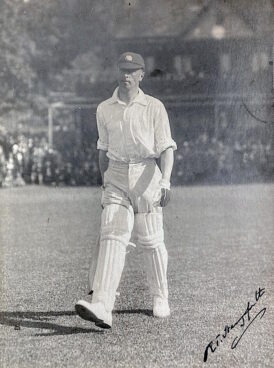

Then last year, an autographed photo of Stanyforth was part of a small stash of memorabilia I bought from a British bookseller, even though I had no particular intention of buying it. At that point I knew Stanyforth’s signature was a rare item. So I decided it was time to head up to the attic, grab my old laptop, and quickly polish up Stanyforth’s story and share it with anyone who was interested.

The first interesting thing I discovered about Stanyforth is that he had never actually played for Yorkshire before being appointed to lead England (or, more accurately, MCC) in South Africa. From there, his Yorkshire career turned out to be limited to three appearances in successive matches in May and June 1928. It seemed strange, and all the more so because, against the traditions of which Yorkshiremen are so proud, Stanniforth was born in London on May 30, 1892. So his Yorkshire debut came as late as his 36th birthday. .

In 1941, Stanyforth married, but the marriage had no children, making a man named Ronald Thomas Stanyforth the last of his line. That in itself may explain, at least in part, why cricket writers have shown little interest in him.

By his background, Stanyforth was a man of privilege, and he was therefore considered a Yorkshireman, and the family seat was at Kirk Hammerton Hall, near York. Stanyforth’s ancestors made a lot of money from business, some of which unfortunately seems to have come from the slave trade.

Stanyforth was the second-born** of two children, but as he was the only son, he ultimately inherited the family fortune. He was educated at Eton and his interest in cricket and many other sports grew there. Always a wicket-keeper, it is worth noting that Stanyforth played in Eton’s first XI but was never selected for a match against another major school. The story was similar when he went to Oxford where he made his First Class debut against MCC in 1914. However, that opportunity marked the only time he appeared in college at that level.

After college, Stanyforth decided to join the Army, even though he didn’t have to work. The First World War was just weeks away, and considering the life expectancy of young officers, Stanyforth was lucky to survive the war. He was clearly a brave man, as he was wounded in 1915, mentioned in despatches in 1917, and awarded the Military Cross.

Remaining in the army when peace returned, Stanyforth remained in Ireland during the period of martial law in 1919 and 1920. From then on, Captain Stanyforth held a more agreeable position, that of 3rd Duke of Gloucester and equerry. Son of King George V.

His career in the military and royal court undoubtedly gave Stanyforth further opportunities to play the game, and he also took part in the MCC. By the early 1920s he was playing at first-class level for both the Army and MCC, and in the winter of 1926/27 he was able to leave military service to tour South America with a strong MCC team led by ‘Plum’ Warner. 53.

All the amateur aspects were pretty good. All had First Class experience and ‘Gubby’ Allen and Jack ‘Farmer’ White went on to enjoy successful Test careers. At that time, the Argentine game was particularly strong, and four matches against the national team were played in first class. The series was also closely contested, but MCC ultimately won 2-1. Warner rated Stanyforth as a ‘keeper’ and wrote in detail about his skills. cricket player. Stanyforth was also the highest MCC scorer in a First-Class match and performed well with the bat, including his highest innings of 91 in the final and decisive match against Argentina.

But South Africa, an established Test nation, was a somewhat different proposition. Warner was undoubtedly the driving force behind the invitation to Stanyforth. Other amateurs who accepted the invitation included Derbyshire’s Guy Jackson, Warwickshire’s Bob Wyatt, Kent’s Geoffrey Legge, Leicestershire’s Eddie Dawson and young Middlesex leg-spinners Ian Peebles and Greville Stevens. Douglas Jardine was among those who failed to accept the invitation.

As far as experts are concerned, Jack Hobbs, Patsy Hendren, Frank Woolley, Harold Larwood and Maurice Tate all refused to give their opinions, but Walter Hammond, Herbert Sutcliffe, ‘Tich’ Freeman, George Geary, Ewart Astill, Sam Staples and Harry With both Elliott (back-up keeper) and Ernest Tyldesley doing so, the team was still a strong side.

The first choice as captain was Jackson, but he withdrew after suffering a nervous breakdown. It was then that Stanyforth was appointed to lead the team and Sutcliffe’s Yorkshire opening partner, Percy Holmes, took Jackson’s place in the party.

The Test series was interesting. Stanyforth’s team won the first two Tests and then drew the third before the home team won the fourth and fifth Tests to square the series. An eye injury forced Stanyforth to miss the final day of the fourth Test and the fifth when Stevens took over as captain at the age of 19, a decision that seemed odd considering Wyatt had also played in the match.

What was the verdict of Stanyforth’s four tests? His batting certainly wasn’t all that shaky, giving up just 13 runs at 2.60 in his six innings. Behind the stumps, he took seven catches and two stumpings. He allowed 50 byes in the seven innings he was behind the stumps. His deputy, Derbyshire’s Elliott, conceded just one bye in the final Test.

So why did Stanyforth suddenly turn out for County in those three games in 1928 when he had never played for Yorkshire before? There is no clear answer, but several factors have been suggested. First Yorkshire’s long-standing ‘keeper, Arthur Dolphin, retired at the end of the 1927 season, creating a vacancy.

Arthur Wood, who had played alone the previous summer, appeared in the first few games of the 1928 campaign, after which Stanniforth had three chances before Wood returned, and indeed for the remainder of the season. War years. In three matches, Stanyforth gave away 61 byes, and although he was slightly better with the bat compared to last winter’s Tests, he still only had 26 runs to show for in three innings.

Do Yorkshire see the 36-year-old as their future captain? Last winter the county was looking for a new appointee for Major Arthur Lupton’s retirement, and with no obvious amateur candidates, Sutcliffe was eventually offered the job, which he politely declined. The 38-year-old William Worsley, who had inherited his father’s baronetcy, became captain, although Stanyforth may have been considered a future candidate.

Despite his age and limited success in South Africa, Stanyforth made one more overseas trip to the Caribbean with England in 1929/30. The starting team, no doubt expecting an easy game after beating the same opposition 3-0 in 1928, chose two players from a generally aging squad – 50-year-olds George Gunn and Wilfred Rhodes – and duly secured a 1-1 draw. Recorded. Stanyforth appeared in four games on the tour, scoring just four runs and making three catches, but was sent home due to a hand injury. Realistically, he had no chance of adding to his four caps. Young Les Ames has featured in every Test and will probably always do so as long as injuries allow.

The trip to the Caribbean was effectively the end of Stanyforth’s major cricket career. There were several more first-class matches for the MCC and Free Foresters, the last of which was in 1933, after which it was club cricket exclusively for men, who left the army in 1930 as a major. From there he returned. To carry out his duties alongside the Duke of Gloucester, he must have had some sort of involvement in the 1936 abdication crisis.

Also in the 1930s, Stanyforth contributed several articles on wicket-keeping: cricket player At the editor’s request, his old friend Warner. There was also a book in 1935 that was just a plain educational text, but sadly it doesn’t give any real taste of the man Stanniforth was.

World War II brought Stanyforth to serve his country once again. In his late 40s, he never saw active service, but was one of the last officers evacuated from Dunkirk. His subsequent role was as a staff officer, and he completed his service as a lieutenant colonel in 1946.

His military career ended and Stanyforth, then a married man, returned to the royal family for a time and also took part in the MCC and, to a lesser extent, Yorkshire. The Stanyforth family, who had become wealthy soon after their father’s death, split their time between Kirk Hammerton Hall and London, and also had a house in Kenya to visit during the winter.

Unfortunately, Stanyforth’s retirement was short-lived. In his later years, he suffered from poor health and died in 1964 at the age of 71. His widow survived him by 20 years, but she did not remain in Yorkshire and Kirk Hammerton Hall and all its contents were sold the following month. Stanniforth passed away.

*England’s youngest captain: the life and times of Monty Bowden and two South African journalists Posted by Jonty Winch, published in 2003

**In fact, I’m sure there’s a lot of evidence, three ways, to support the claim that I had an older sister who grew up and spent her entire life in France.