Editor’s note: Eight years ago, on the eve of the 2016 election, Mother Jones published a story by Arlie Russell Hochschild, a renowned sociologist who had spent five years interviewing a group of white Southern conservatives to understand what drives the way they see America, politics, and Donald Trump.

Trump was not the focus of Hochschild’s research, but she soon discovered that he was there in the background, tapping into the “deep story” her interviewees told about themselves and their community. They saw themselves, she wrote, as waiting patiently in line for their shot at the American Dream—but others, whom they saw as undeserving and who were often Black or immigrants, were cutting in line. “The government has become an instrument for redistributing your money to the undeserving,” they believed. “It’s not your government anymore; it’s theirs.”

It didn’t matter if that story was factually true (Hochschild documented that it was not): It drove how people felt and how they would ultimately vote. It gave them an explanation for why the success they had been told was their birthright seemed elusive, why their families might even need benefits like food stamps or disability income that they had been told only the weak would accept.

“Trump solves a white male problem of pride,” Hochschild wrote. “Benefits? If you need them, okay. He masculinizes it. You can be ‘high energy’ macho—and yet may need to apply for a government benefit. As one auto mechanic told me, ‘Why not? Trump’s for that. If you use food stamps because you’re working a low-wage job, you don’t want someone looking down their nose at you.’”

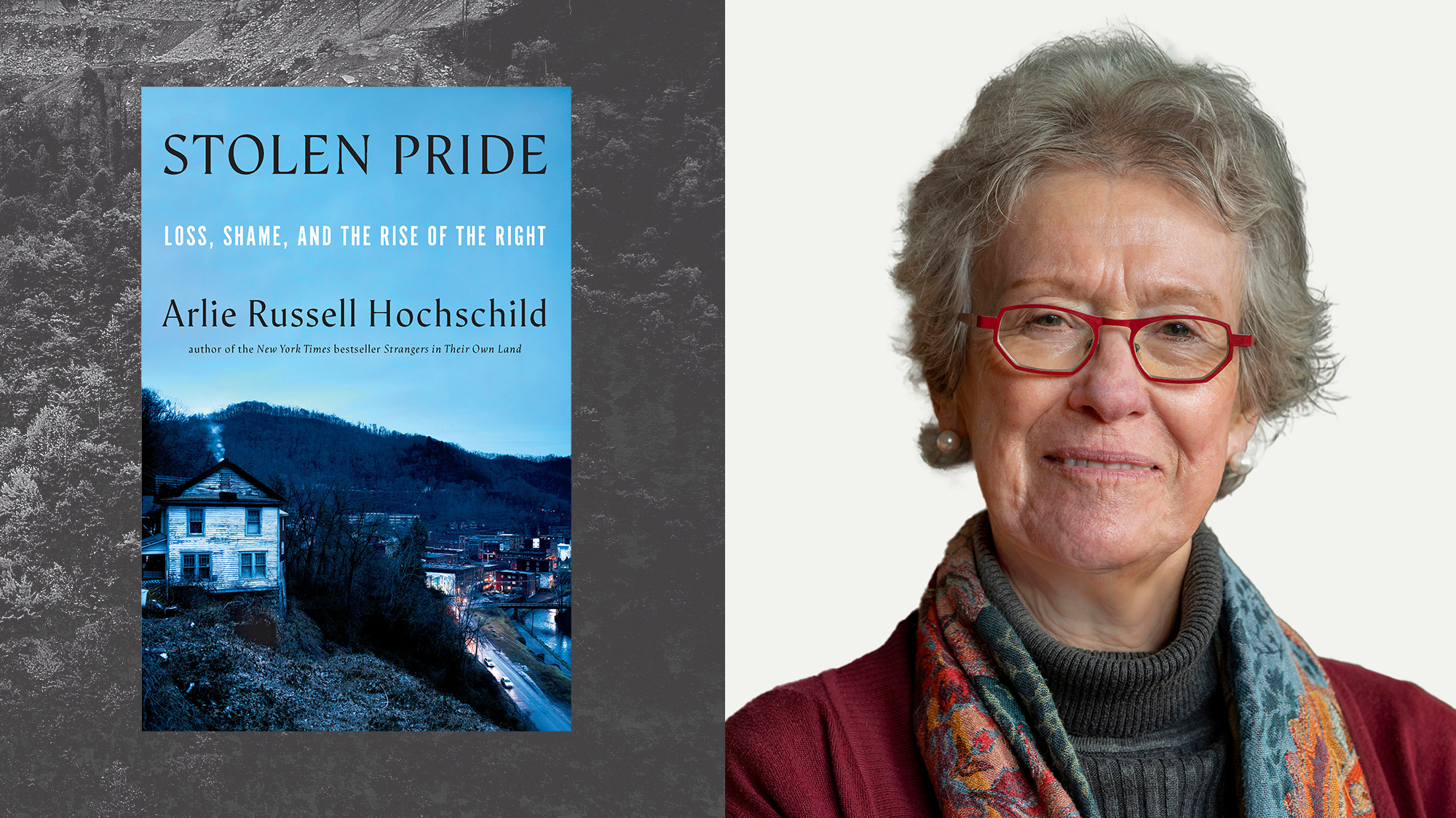

Trump would not, of course, deliver on these voters’ economic needs. But he would deliver on their need for pride. And it’s that issue that Hochschild returns to in her new book, Stolen Pride, set in the heart of what Trump calls the forgotten America—the town of Pikeville, Kentucky.

In 2017, when Hochschild’s research for this book began, Pikeville was the site of a neo-Nazi march that became a prelude for the deadly rally in Charlottesville, Virginia. The march was a focal point for Hochschild’s interviews with everyone from an imprisoned white supremacist gang member to a self-described “trailer trash” TikTok creator. In Pikeville, the deep story was all about what Hochschild came to call the pride economy.

“We live in both a material economy and a pride economy, and while we pay close attention to shifts in the material economy, we often neglect or underestimate the importance of the pride economy. Just as the fortunes of Appalachian Kentucky have risen and fallen with the fate of coal, so has its standing in the pride economy…

“And our place in the material economy is often linked to that in the pride economy. If we become poor, we have two problems. First, we are poor (a material matter), and second, we are made to feel ashamed of being poor (a matter of pride). If we lose our job, we are jobless (a material loss) and then ashamed of being jobless (an emotional loss). Many also feel shame at receiving government help to compensate that loss. If we live in a once-proud region that has fallen on hard times, we first suffer loss, then shame at the loss—and, as we shall see, often anger at the real or imagined shamers.”

In places like rural Kentucky, that sense of shame and lost pride is connected to what Hochschild identifies as the paradox of the American Dream: A self-sufficient, middle-class life has become harder to attain in many rural, conservative communities—but people in those communities are more likely to blame themselves for this.

“From roughly 1970 on, the United States gradually divided into two economies—the winners and losers of globalization. Rising in opportunity have been cities and regions with diversified economies, often the site of newer, less vulnerable industries, which typically hired college-educated workers in service and tech fields. Declining in opportunity have been rural and semi-rural areas, offering blue-collar jobs in older manufacturing industries more vulnerable to offshoring and automation. These also include regions where jobs are based on extracting oil, coal, and other minerals, the demand for which fluctuates with world demand.

“The urban middle class, which leans Democratic, has become a so-called mobility incubator, while many rural blue-collar areas, now leaning Republican, have become mobility traps. Between 2008 and 2017, one study found, the nation’s Democratic congressional districts saw median household income rise from $54,000 to $61,000, while incomes in Republican districts fell from $55,000 to $53,000…The second part of the paradox lies in core ideas about hard work and individual responsibility for one’s economic fate.

“When asked in a national survey why it is that a person ends up being poor, 31 percent of Republicans (party members or those who lean that way) say it is due to ‘circumstances beyond their control,’ in contrast to 69 percent of Democrats. Similarly, 71 percent of Republicans but only 22 percent of Democrats think ‘people are rich because they work hard.’…Thus, people growing up in the two kinds of economy experience different degrees of moral pinch between the cultural terms set for earning pride and the economic opportunity to do so.”

It’s this moral pinch—being caught in a declining regional economy while being told you have yourself to blame for your economic struggles—that the people Hochschild interviews describe from a variety of angles. For some, it fuels hate; for many, resentment; for all, a kind of bewilderment.

Like Hochschild’s 2016 book, these stories are even more timely now than they were when she conducted the interviews, in part because of Trump’s running mate selection of JD Vance, whose fame began with his book, Hillbilly Elegy. But where Vance concludes that the fix for places like Appalachia is to exclude others from the economy—both the material and the pride kind—Hochschild’s interviewees offer more nuanced views. All but one reject the white supremacists marching through their town. But many also are drawn to the way Trump and Vance make them feel seen. She talks with TikTok creator David Maynard, born literally yards away from Vance’s ancestral hometown of Jackson, Kentucky, and his wife, Shea, who show her the places where they grew up, fell in love, and built a life together. It’s a “reverse Hillbilly Elegy,” Hochschild writes, a story of wrestling with the paradox of the American Dream.

“If I’m a Moore’s Trailer Park white trash person, the only narrative I have tells me that I’m white, so I’m privileged,” Maynard tells Hochschild. “That’s the something I have and that must put me ahead. But what if it doesn’t put me ahead? I’m left with nothing because I’m lazy and stupid. There’s no excuse. If you’re white and poor, people think, ‘What’s wrong with you that you’re stuck at the bottom?’”

Another of Hochschild’s interviewees, Tommy Ratliff, digs deeper into that sentiment: “I could have become a white nationalist,” he tells her. Why that’s so, and how he didn’t, is the subject of the chapter excerpted below. —Monika Bauerlein

“In college,” Tommy Ratliff told me, “we had a guest speaker who gave us a lecture on the American Dream. He told us all we had to do was to work real hard, stick to a plan, and open a bank account. We should save a little money each month for our kids’ future education. At the time, I was earning $9.50 an hour behind the counter at a hobby shop and had to repay a loan I took out to pay for college and child support. Part of me just felt like telling the guy, ‘Shut up.’”

A tall man with long, wavy brown hair fanned across broad shoulders, gentle and direct in manner, Tommy was wearing his favorite black T-shirt, which said, “Not perfect, just forgiven.”

“Maybe I could earn my way to the American Dream if nothing else went wrong. That’s if I don’t get sick, if I don’t need a new heat pump, if my electric bill weren’t $400 a month, if my ex-wife didn’t get hooked on drugs, if my parents weren’t alcoholics, if my disturbed brother didn’t move in with me and raid my refrigerator while I was at work. Sure, the American Dream is all yours if nothing goes wrong. But things go wrong.”

Tommy explained what that meant as we walked through maple, redbud, and pines around his natal family’s quietly sheltered valley enclave. We walked by the home of his Uncle Roy, now widowed and seldom home. Roy had gotten Tommy out of scrapes, bought him a car, lent him money. Roy’s wife, Tommy’s aunt, became the “one I was closest to” when words became slurred and voices were raised in his own home next door.

We passed a shed used by Tommy’s paternal grandfather, now deceased, a former miner and World War II vet who had been at Iwo Jima as American GIs raised the flag. He had been decorated with a Purple Heart, long proudly kept like a holy icon in a glass cabinet in his grandfather’s hallway. A nearby shed held his grandfather’s beekeeping equipment and a wooden cane he had made in his retirement, together with a long wooden chain miraculously carved from a single piece of wood.

Visiting the small hillside cemetery near the end of a logging road where Tommy’s ancestors were laid to rest, we ran into Tommy’s Aunt Loretta washing family gravestones and restaking the VFW flag by his grandfather’s grave. A retired nurse, Loretta enjoyed Civil War reenactments but was uninterested in Pikeville’s upcoming white nationalist march. “Those guys come and go. I don’t pay them mind,” she said.

“The very idea that I had a place on a class ladder came to me slowly,” Tommy mused. “First, I thought of my family as middle class, and I was proud of that. As a kid, class was a matter of the kinds of toys I got at Christmas. Don’t get me wrong. I was happy to get what I got—GoBots, Action Max, Conan the Barbarian, Turok, the Warlord. But the kids at school had better-made versions of the toys I got. So, in toys, I felt somewhere below the middle.” Then when Tommy’s mother’s Texan relatives came to visit, he said, “I could see they looked around and thought my mom had married down and felt sorry for us. One cousin asked me, ‘What do you think a redneck is?’ and I wondered why she asked me that. Did she think I was one?”

We walked along a dirt path to a gurgling stream in back of Uncle Roy’s and Aunt Loretta’s homes—a wondrous wooded childhood haunt, filled with pine, poplars, birch, and pawpaw trees, that Tommy had long ago christened “Fairyland,” a term he still used with reverence.

“After 14 or 15, I used to spend a lot of time in this forest,” Tommy recalled, looking around at the trees as if at the faces of dear friends. “George (a childhood pal) and I would fight monsters and trolls and orcs and talking animals, like we saw in films about Narnia. We wore rounded strips of tree bark as body armor and used sticks as swords. I’d catch salamanders, frogs, and crawdads from the stream and let them go. We didn’t fish or hunt; we thought everything should be left the way it is. If you listened really close to the crickets and frogs sing to each other at night, first a song would come from one bank of the stream, then we’d hear an answer from the other. In the winter, we’d walk up the frozen streambed on the ice, then slide all the way down.” Listening to Tommy, I was reminded of a passage in Wendell Berry’s Jayber Crow: “Aunt Beulah could hear the dust motes collide in a sunbeam.”

“Growing up, my world was real small—Elkhorn, Dorton, Belcher, Millard, Lick Creek, places around our holler. I didn’t know what was going on outside my family and neighbors and these places,” Tommy said. “Elkhorn only had one red light, but it was a city compared to Dorton, nothing there except the school and a pizza place. Dorton was tough. In a lot of hollers, people only come out once a month (to shop or visit) and don’t like outsiders. Nearly everyone in my world—my parents, my two brothers, my best friend George, my neighbors and schoolmates, and the action figures we played with—were all white.”

When, after finishing high school and working a few jobs, Tommy enrolled at Clinch Valley College in Wise, Virginia, he made his world smaller still. “Dad never liked me or my brothers to talk. If we were at dinner, he told us, ‘Don’t talk.’ If we were in the car, it was ‘Don’t talk.’ If we had company, ‘Don’t talk.’” So at Clinch Valley, Tommy sat in the back of a large classroom, was assigned to no discussion group or advisor, feared going to his professor’s office hours, and never talked. At the end of the first semester, Tommy flunked out, imagining that he, not the college, had failed.

“I’m not sure if I wasn’t paying attention or if it wasn’t taught. But before college, honestly, I wasn’t very sure how Blacks got to America,” Tommy told me. “I learned about slavery from seeing Amistad (a film about a slave ship rebellion in 1839) and 12 Years a Slave (about a free Black man kidnapped and sold into slavery), and about the Holocaust from Schindler’s List.”

Tommy also learned about Black life through television: “For a while, we didn’t own a TV. Dad would rent one in his name and when the bill got too high, Mom would put it in her name. I watched The Cosby Show and thought those kids were a whole lot better off than I was. They got an allowance, and all they had to do was save it. Their parents didn’t yell or drink. They lived in a nice house, and the dad was fine with them talking.”

Yet in one program about Black family life, Tommy suddenly recognized his own. “I watched and loved every episode of Good Times,” a 1970s sitcom about a Black family in Chicago that struggled with such things as job losses, a car breakdown, and an eviction notice. “In one scene,” Tommy recalled, “the wife, Florida, is talking to her girlfriend, who confides, ‘I can always tell when it’s Saturday morning because I wake up with a black eye.’”

“What got me wasn’t the story. It was that people laughed at it. Florida’s friend laughed. Florida laughed. On the TV soundtrack, the audience laughed. As a kid, I remember wondering: Why did they all laugh? At night, I’d crawl into bed with my older brother. I could hear my dad downstairs drunk, yelling and cursing at Mom, hitting her, shoving her against the wall, and shouting, ‘That didn’t hurt!’ Mom was yelling at Dad, ‘Stop it!’ I was scared. I wanted to cry.”

As Tommy grew up, his parents’ lives spiraled. “In the 1980s, when I was in high school, Dad lost his job guarding a mine and got a job as a supervisor in a lumberyard. When the lumberyard closed, Dad worked for my Uncle Roy’s road crew cutting grass along public roads with a dozer at minimum wage. That’s when we fell behind in taxes. When my father fell off the dozer and injured his back, his doctor discovered he had cancer.” As funds ran down, Tommy said, “we went from three cars to one, which we could barely keep running. We applied for food stamps, which bothered my dad terribly. I wondered: Had we become that class of family? We felt ashamed.”

Then Tommy’s parents began to drink themselves farther downward. “Dad drank Early Times whiskey with Tab and Mom drank vodka with Sprite—all day long. By 6:00 p.m., I’d try to leave. They argued. Mom would cry. Dad would get mad at her crying. That’s when I heard him shout, ‘That doesn’t hurt.’”

The family house fell into disrepair and his parents moved out of it into a trailer, then asked to move in with one troubled son after another until, one by one, they died.

In the wake of his parents’ decline, Tommy’s own ordeal unfolded. An acquaintance asked him if she could move into his trailer to save on rent. The two became involved, she became pregnant, and at 19, Tommy married and briefly imagined he was glimpsing a life of satisfaction and pride. “I got baptized at the Free Will Baptist Church in a creek one midnight in December, total immersion. One man held my back, another my head. It was cold and I got sick. When I got better, I got a union job at Kellogg’s biscuit factory. We moved near her folks in Jenkins, and I thought, ‘For my American Dream, this is good enough,’ and it would have been if she’d been the right woman.”

But she was not. The baby was too much for her. The house was left in disarray. Tommy’s addicted brother moved into a spare room. Returning late from his job at Kellogg’s, Tommy had a head-on collision. When, after his medical leave, he tried to return to his job, Kellogg’s fired him.

Jobless, with a wife and child to support, with $225 due monthly for rent and $100 for power, Tommy began scavenging aluminum cans out of ditches to recycle, $25 per bunch. Other luckless neighbors competed for the good cans. “I knew people looked down on me because I knew how I looked at other people scrounging cans. But part of me still thought, ‘I’m not that kind of person.’ I’d spend a few hours visiting with Uncle Roy before I got around to asking to borrow money. He’d know why I came, which was embarrassing. I’d borrow his car if mine broke down or I was driving mine with dead tags. I looked for work, but you had to pass the drug tests first, and for a while, I was trying muscle relaxants, Valium, Ativan. Then it got to half a case of beer, then more.” After Tommy’s marriage dissolved, his loving and nondrinking in-laws took in Tommy’s son. Now, with Tommy on his own, his heavy drinking grew worse, from occasionally to every day, from with someone else to alone, to alone and a lot.

Drinking had its own pride system, Tommy discovered. “At the top were guys who could hold a lot without getting sloppy drunk, pay for the drinks, and share the high. In the middle ranks were angry drunks. There was a rule to never talk politics, so angry drunks would be mad at ‘the man keepin’ us down.’ At the very bottom of the hierarchy were the crying drunks. I was a crying drunk.”

Our walk through Fairyland was taking us to a cluster of branches, a long-ago-collapsed teepee Tommy and his pal George had once built as boys in a moment of childhood triumph, and Tommy began to relate the hardest moment of his life. “We all have different bottoms,” he reflected softly. “I reached my bottom when I overheard my dad—whom I’d always assumed was my real dad—call me his stepson. I was shocked; I’m not his real, biological son? Maybe that’s why he never liked me, seemed prejudiced against me. I’m the wrong blood and can’t do a thing about it.

“The world went dark. I gave up. All I saw was a wall of night. I had failed. That was my bottom. I was drinking alone, a quart of whiskey a day. I dreamt of driving fast into oncoming traffic. I had an appointment with a doctor to check on the beginning stage of cirrhosis of my liver. I was heading toward my own death.”

One of Tommy’s favorite musical artists was Jelly Roll, a white, Tennessee-born rapper who put Tommy’s feelings into words:

All my friends are losers.

All of us are users,

There are no excuses, the game is so ruthless. The truth is the bottom is where we belong.

In Deaths of Despair and the Future of Capitalism, Anne Case and Angus Deaton report a surprising finding: Although the United States had long been among the world leaders in extending its citizens’ life spans, since the turn of the 21st century, there has been an unexpected rise in premature deaths of white people in the prime of life, ages 45 to 54. The main causes are death by drug overdose, suicide, or alcoholic liver disease, which together claimed the lives of 600,000 people between 1999 and 2017. Especially hard hit have been white, blue-collar men without a bachelor’s degree.

Such men were not dying in heroic wars, battling fierce storms at sea, or toiling in coal mines. One by one, they were—and are—dying in solitary shame. In the obituary section of the Appalachian News-Express, I began to notice death notices showing young faces, sometimes listing young ages, but nearly always omitting the cause of death.

Tommy could name a number of local suicides. “The younger brother of a fifth-grade friend of mine shot another and then himself in the head. One guy drove drunk into a tree. My own brother Scott drove drunk off the road, and I believe that was a suicide. At one point, you could have almost counted me.”

Tommy remembers reading Christian Picciolini’s White American Youth: My Descent Into America’s Most Violent Hate Movement—And How I Got Out, the autobiography of a boy who was converted by a neo-Nazi. Picciolini was 14, smoking pot with a pal in a Chicago back alley, he writes, when a man in a muscle car drove up, stopped, and got out. The friend fled, but the man confronted the young Picciolini, took the joint out of his mouth, and said, “Don’t you know that’s exactly what the communists and Jews want you to do, so they can keep you docile?” By 16, now clean of drugs and with a purpose, Picciolini had become the leader of a group of Chicago-area skinheads, which he then merged with the yet more violent white supremacist Hammerskins.

“If I had been 14 and smoking in an alley and a man showed interest in me,” Tommy mused, “what if he dressed in camo, wore his ball cap back to front, and took me in? What if I began spending time at his house to get out of mine? And if my dad was beating me hard, and my parents were drinking, and I felt like they didn’t really know me or care? I ask myself: What would have happened? I could have felt the guy in the muscle car really cared about me.

“And what if that guy told me, ‘Your dad lost his job at the lumber mill because immigrants were coming in, or because a Jew closed it down’? I might have said, ‘Oh yeah,’” Tommy continued. “Or when I was going out with Missy (a mixed-race girl whom he invited to senior prom), what if he’d said, ‘Missy dumped you for that other guy. Black girls do that’? I might have said, ‘Oh yeah.’ Or when I flunked out of Clinch Valley community college and I couldn’t go home—my stepdad had converted my bedroom into his hobby room to make fishing lures—the man could have said, ‘Colleges are run by commies.’ I might have said, ‘Oh yeah.’”

In these ways, Tommy speculated, an extremist might offer recruits a raft of imagined villains onto whom to project blame and relieve the pain of shame. David Maynard had focused on a missing national narrative that might protect poor whites from the shame of failing to achieve the American Dream. Tommy was focused on something else: the shamed person’s vulnerability to those offering to blame a world of “outside” enemies.

On the third day of Tommy’s detox, he walked outside and seated himself on a patio chair, miserable. “My head was hung low, and I was staring at the ground between my legs. Then I suddenly noticed a trail of ants. Each ant was carrying a tiny load—a crumb, a bit of leaf, a piece of dirt. Then I saw it: One ant was carrying another ant as big as he was. That dead ant was useless, not doing its part, being a load instead of carrying a load. I thought, ‘See that dead ant? That’s me, right there. I could be that carrier ant. I do not want to be that dead, carried ant.’ That was one of the greatest moments in my life. That carrier ant brought me back.”

The Latin term prode, “to be of use,” is the origin of the word pride. Tommy’s grandfather had been honored for his bravery in the mines and on the battlefront. He was a carrier ant. For Tommy, it would be through helping others out of drink and drugs that he was to carry a load himself.

Tommy had hit bottom: shame. But he had rejected the temptation to shift blame to all the racial targets offered up to him and had come to see how blame, placed like a covering over disappointing life events, might falsely seem to relieve his pain. He was to find his way forward to creative repair. By the time I was walking with Tommy through Fairyland, he had happily remarried to a medical researcher and earned a bachelor’s degree, graduating on the dean’s list. He’d also taken a job at the Southgate Rehabilitation Program, where he counseled recovering addicts.

Imagining the leader of the upcoming march, Tommy reflected, “That guy’s selling white nationalism as a quick fix to make a guy who’s down on himself feel like he’s strong and going places. With racism, that guy would just be handing anyone like I was another drink.”

In 1996, Purdue Pharma had 318 sales representatives. Four years later, the number had risen to 671. It dispatched 78 sales representatives to Kentucky alone. In 2000, Kentucky had only 1 percent of the US population, but it had a higher than usual proportion of coal miners who had suffered injuries and needed pain relief, and it was one of the regulation-averse states Purdue focused on. For each drug purchase, such states called for only two receipts documenting the purchase—one for the pharmacist, a second for Purdue. More closely regulated states, mostly blue states, called for three copies—the third going to a state medical official monitoring the prescribing of controlled substances.

The requirement of that third copy had an astonishing effect. As later research would reveal, distribution of Purdue’s opioid pain medication OxyContin was 50 percent higher in the loosely regulated states (requiring two copies per drug purchase), such as Kentucky, Tennessee, and West Virginia, than it was in more tightly regulated states (requiring three copies per purchase), such as New York, California, and Illinois.

Within these “freer” states, Purdue targeted doctors who were already prescribing large amounts of opioids and the pharmacists from whom those high-prescribing doctors ordered drugs. Health care professionals were given OxyContin fishing hats, stuffed plush toys, and music CDs (Get in the Swing with OxyContin). Purdue offered free, limited-time prescriptions for a seven- to 30-day supply of OxyContin—a drug that, it was found later, produced similar withdrawal cravings and symptoms as heroin. Crucially, Purdue offered its salespeople large bonuses for increasing OxyContin sales. In addition to the average sales representative’s annual 2001 salary of $55,000, annual bonuses ranged from $15,000 to nearly $240,000.

In 1996, when the company first introduced OxyContin, sales were $48 million. By 2000, sales had hit $1.1 billion.

In 2021, the rate of deaths from drugs in the United States was 32 per 100,000. In Pike County, the rate was 91 per 100,000. Between 2016 and 2018, Kentucky had the nation’s highest rate of children living with relatives other than their parents—9 percent. Another 5 percent were in foster care.

Through Tommy Ratliff, I met one of the men he counseled, James Browning, and I asked James how drugs had affected his sense of pride. He answered with a clarity he credited to his recovery. “I felt shame about some things that happened to me when I was a kid. To hide from my shame, I turned to drugs. Then I was ashamed of being on drugs. So I was part of a shame cycle. I took drugs to suppress shame, then felt shame for taking drugs. I disappointed my mom. I destroyed my marriage. I hurt my kids. But with Tom Ratliff’s help, for the first time in my life, I recovered from my fear of shame.”

Looking back at his descent into drugs, James observed how he had slipped down a hidden status hierarchy among fellow users, parallel to that Tommy Ratliff had discovered among the inebriated. “At the top of the hierarchy was the guy who can manage his drug habit and not get caught, and at first, I was that guy. I thought drugs were an adventure. I tried marijuana at 14, moved to pain pills in high school, and said to myself, ‘I’m just doing pills.’ Then when I was a husband and father and could hold down a job, I was proud of managing my habit. Then I was a divorced father. When my ex-wife wanted to move eight hours’ drive away to live near her sister, I moved into a drug house with five buddies and began my homelessness.

“We worked out our own way of judging ourselves and other addicts,” James commented. “When I was snorting oxycodone and hydrocodone, I told myself, ‘I’m just snorting. I’m holding down a job. I’m not a junkie.’ And that worked for a while. But then I got dopesick and I wasn’t holding down a job. And a guy came around, obviously a heroin pusher, and said, ‘Hey, I can make you feel better.’ But we looked down on heroin, and my buddies and I told him we were broke and ran the guy off. But in a few weeks, I was dopesick again and the pusher came back saying, ‘I’ll give it to you free.’ We took some heroin and felt better for a while.

“Then I told myself, ‘I’m snorting heroin, not shooting it.’ I snorted heroin for four or five years telling myself, ‘If you snort, you’re okay, but if you shoot up, you’re a junkie.’ But then I found the effect was stronger if it was shot into me. I didn’t like needles, so I asked a girl to shoot it into me, and I wasn’t shooting it myself, so that was better. But then two years later, the day came when I shot myself up. I became a junkie.”

Shortly after James had arrived at an emergency room unconscious from his fourth heroin overdose, the phone rang in the apartment of his sister, Ashley, a graduate student at the University of Tennessee. “I’d received emergency calls three times before, and every time my phone rang,” she would tell me later, “I dreaded it would be the call: ‘James is dead.’”

This time, the medics had found James without a pulse. But they had done CPR and revived him. “I just sobbed,” Ashley recalled. “I took a breath, got online, and spoke to James: ‘James, are you ready this time?’ He said, ‘I’m so sorry, Ashley; yes, I’m ready.’” In treatment, James recalls, “Tom told us about how he hit his own bottom and saw the line of ants, each carrying its tiny burden, one live ant carrying a dead ant. I understood. Tom Ratliff became the carrier ant willing to carry the dead—or nearly dead—ant. Me.”

This article is adapted from Stolen Pride: Loss, Shame, and the Rise of the Right (New Press), by Arlie Russell Hochschild.