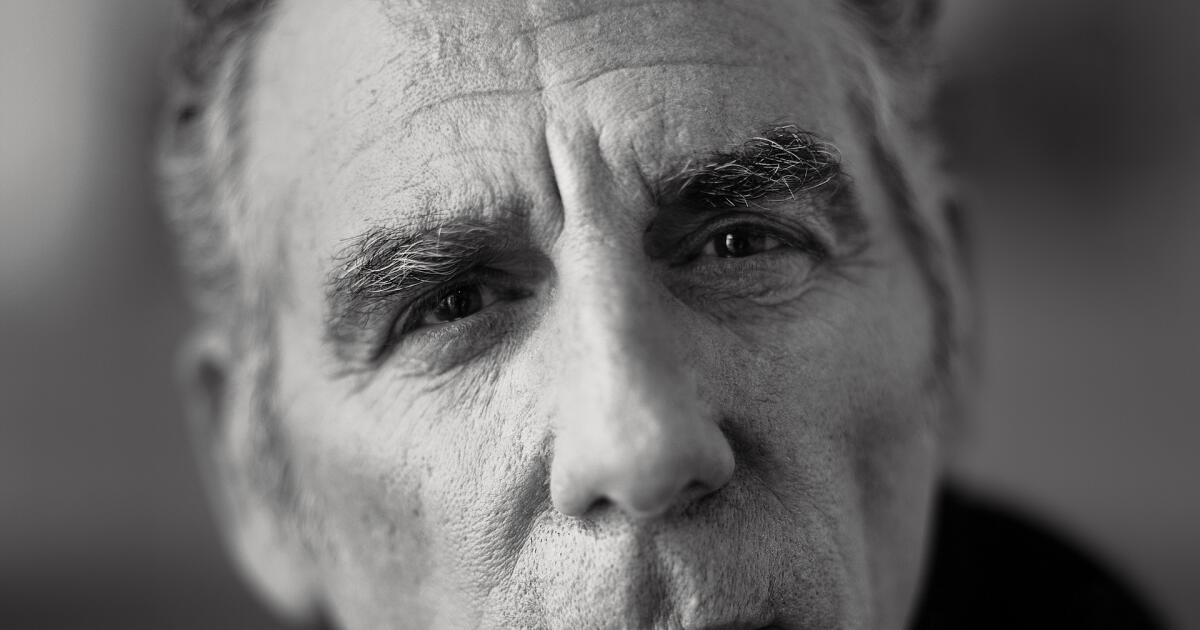

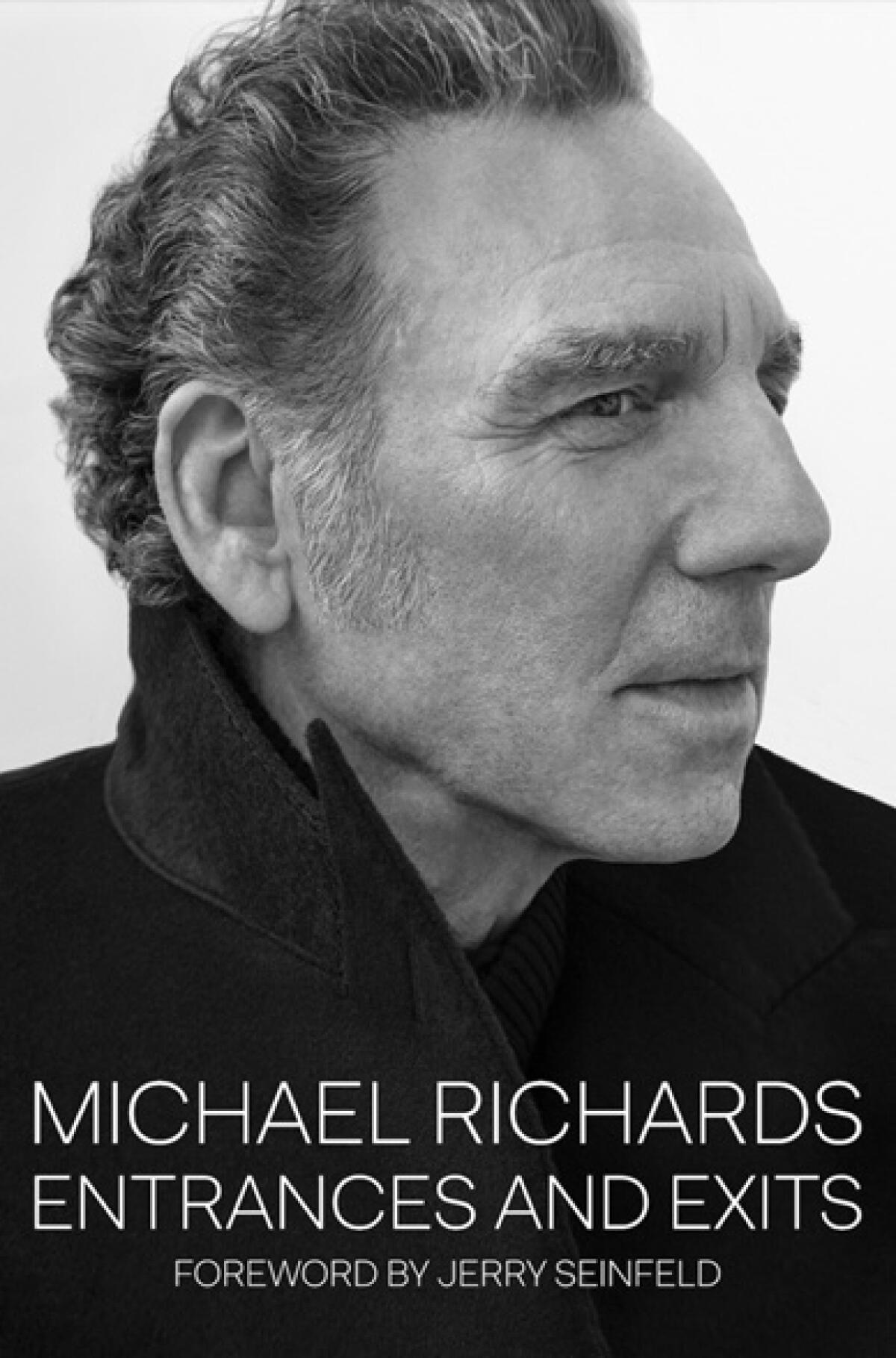

Michael Richards, who rose to fame as Kramer in the popular sitcom ‘Seinfeld,’ releases his memoir, ‘Entrances and Exits.’

(Marcus Ubungen)

on the shelf

entrance and exit

michael richard

Permuted Press: 440 pages, $35

If you purchase a book linked to on our site, The Times may receive a commission from: Bookshop.orgThat fee supports independent bookstores.

Michael Richards entered the cultural consciousness and the apartment next door with the force of spontaneity that was Cosmo Kramer. He was Id free of the rubber legs and chains of “Seinfeld,” the most popular sitcom of its time and a cultural phenomenon that was wildly cult but too big to be considered a real cult. Richards and Kramer worked without a net. Energy, movement, Cavorca forever closer to chaos. But the chaos had a purpose and it was hugely popular. Richards won three Emmys for the role and regularly got the biggest laughs on the show.

Then, late one night in November 2006, chaos turned into disaster. After a surprise performance at Los Angeles’ popular comedy club Laugh Factory, Richards responded to several hecklers with a vicious and ugly tirade. He continued to throw the N-word, turning an uncomfortable night of comedy into the kind of career-destroying incident. These were the early days of the era of ubiquitous cell phone cameras, when a terrible mistake could be instantly transmitted around the world. Richards quickly pivoted to damage control, appearing to apologize via satellite during his friend Jerry Seinfeld’s visit to “The Late Show With David Letterman.” But the damage was done. Now he has been widely labeled as a racist and worse.

Richards recounts his infamous night in his new memoir, “Entrances and Exits,” and apologizes once again. The pop culture mulch machine will quickly turn your book into a soundbite following: “Michael Richards says he is not a racist!” But the Laugh Factory incident is just one tendril in Richards’ book regarding dangerous high-wire performance behavior in general and stand-up comedy in particular. It’s the story of a working mother, a grandmother with schizophrenia, and a very lonely child growing up on the streets of Southern California. On his stage, he finds his life’s purpose, pours everything into his craft, and rises to the pinnacle of his profession, but never learns to control his anger, burns out in a terrible way, and slowly rebuilds himself. It has begun.

It’s also a reminder that everyone is more than the worst thing that’s ever happened to them, and that stability and comedy don’t always go together.

“This is what I call irrational,” Richards, 74, said in a phone interview from his Los Angeles home. “We are constantly challenged. And in the midst of it all, there is anger. So there is always continuous effort with me. “We are constantly trying to be rational, but we are always irrational, there are always mistakes, there are always mistakes.”

Michael Richards wrote in his memoir about his response to his racist Laugh Factory rant: “Public censure and humiliation are forms of justice.

(Marcus Ubungen)

Before Kramer, before public shame, there was a kid wandering around Baldwin Hills wondering who his father was and what happened to him. The kid soon discovered that he loved performing in theater classes. It gave him a way to channel his inner turmoil and anxiety and make people laugh. But the child still felt uneasy. He studied acting at the California Institute of the Arts, created absurdist, physical comedy with his friend Ed Begley Jr., and was drafted into the army in 1970. Stationed in West Germany, he participated in the V Corps Training Road Show. He played the role of the troupe’s colonel. He stayed in character around the clock until he obtained a fake official military ID. It was the beginning of his lifelong obsession with creating and inhabiting personas.

In 1989, when fellow former “Fridays” writer and cast member Larry David and Seinfeld asked her to audition for a new series called “The Seinfeld Chronicles,” Richards was ready to roll. Originally called Kessler, most of his characters appeared on the page. But Richards made him a playful three-dimensional creature, right down to the clothes on his back.

“Everything Kramer wears is handpicked by me,” Richards said. “I scoured every thrift store in Southern California for packs of shirts and put together that closet. Not all of the clothes are from the 60s because my character still wears most of the clothes she wore back then. That’s why pants are short, etc. Because that person is a little taller. Everything about the character is justified.”

In “Entrances and Exits,” Richards writes that although he was also a creature of comedy clubs throughout his career, he always thought of himself more as a character actor or performance artist than as a comedian. His behavior was never scripted and was generally wild, including falling over tables, walking on stage, playing with microphone stands and walking away. In the book, Richards uses the word “knockabout” several times to describe his own school of comedy. But he was also quite disciplined. Between seasons of “Seinfeld,” he often took time off from studying acting in New York to hone his craft.

On stage, Richards typically went where his soul moved him. And the mind can become dark and unpredictable. He was friends with Sam Kinison, a comic whose entire act was based on anger, and there was a time when Kinison surprised Richards with the diamond-like purity of his anger. Richards wrote of his initial impressions of Kinison: “I think he’s crazy. I think I’m going in the same direction.”

In 2006, “Seinfeld” was in the rearview mirror. Richards’ follow-up series, “The Michael Richards Show,” was abruptly canceled in 2000. He drifted a little and dipped his toes back into stand-up. On November 17, 2006, he appeared on the Laugh Factory stage later than usual. He was uneasy, shifting from angry comedian mode to erratic performer and unhappy human being. Then he heard a voice from the balcony: “We don’t think you’re very funny!”

“Of course, looking back, I wish I had agreed with him,” Richards wrote. “‘Okay, it’s not that funny tonight. Is there anything I can do? Do you wash your car and mow the lawn? I don’t want you to leave dissatisfied.’ Instead, I take his word for it pretty hard. He’s got a powerful punch under his belt.”

And he shouted loudly and furiously, using the ugliest language known to man.

Yes, I’m sorry. And he accepts the resulting descent into purgatory. “Public censure and humiliation are forms of justice,” he wrote. And nothing about his personal rehabilitation seems simply performative. Richards spent several years after Laugh Factory off the stage and learning to live on his own (although he still welcomes the occasional acting gig). He studied the Hindu philosophy of Vedanta in Cambodia. He and his second wife, Beth, had a son, and he eventually enjoyed watching “Seinfeld” with his son. (For years he was tormented by thoughts of how much better his acting could have been.) He fought, and for a time beat, prostate cancer.

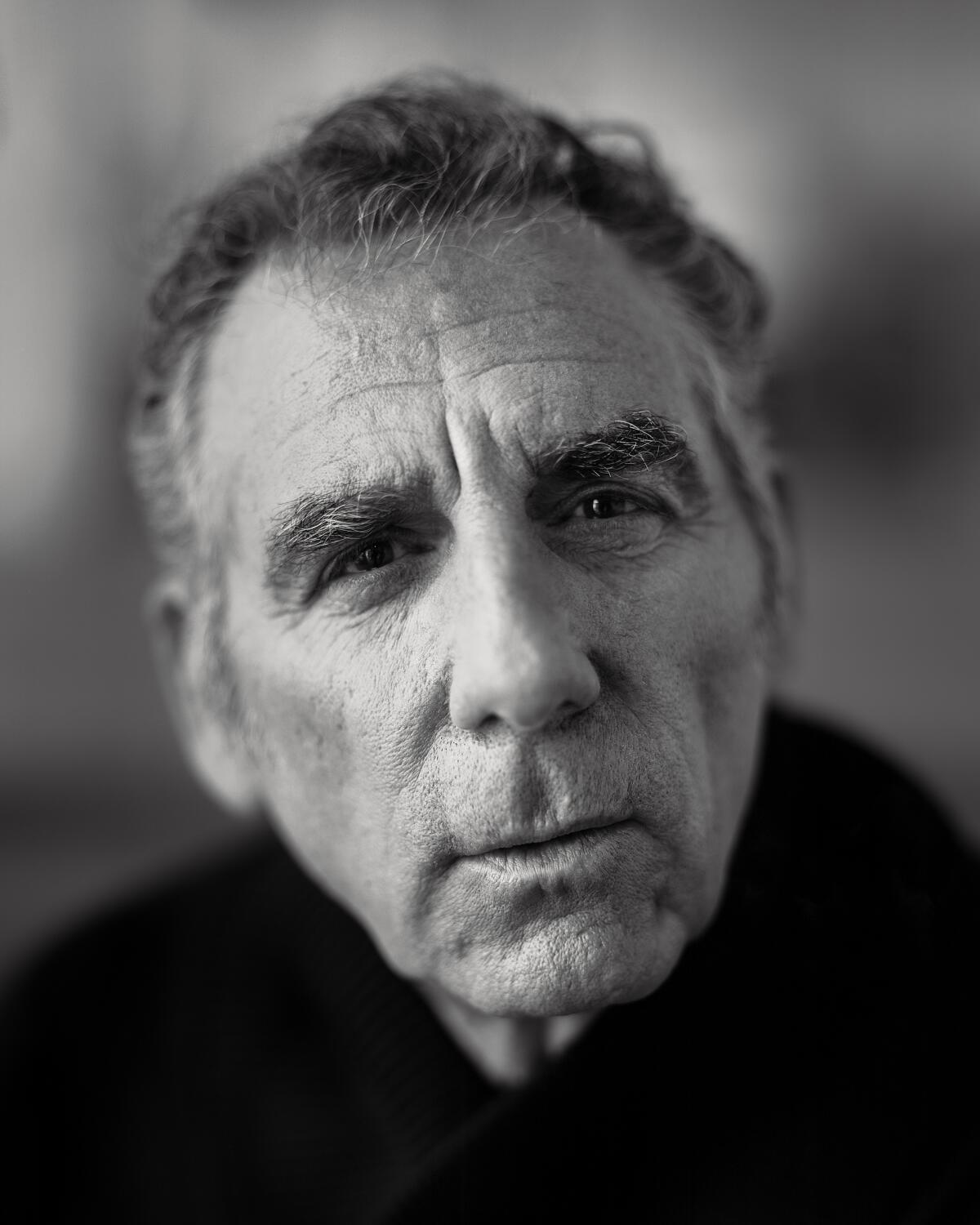

Michael Richards says these days, “I sit with the natural world that seems to be behind so much of everything we do.” His memoir ‘Entrance and Exit’ was published on June 4.

(Marcus Ubungen)

He is willing to continue what he calls “the work of the heart” – finding out who he really is and what drives the darkness inside him. Like the kid who once roamed Baldwin Hills, he walks the mountains of Southern California every day. “I want to get behind words, anger, people, cultural conditions, etc.,” he said. “So I sit with the natural world that seems to be behind so much of everything we do.”

Asking for forgiveness can get boring. “Entrance and exit” is something else. It is a description of life and its accomplishments.