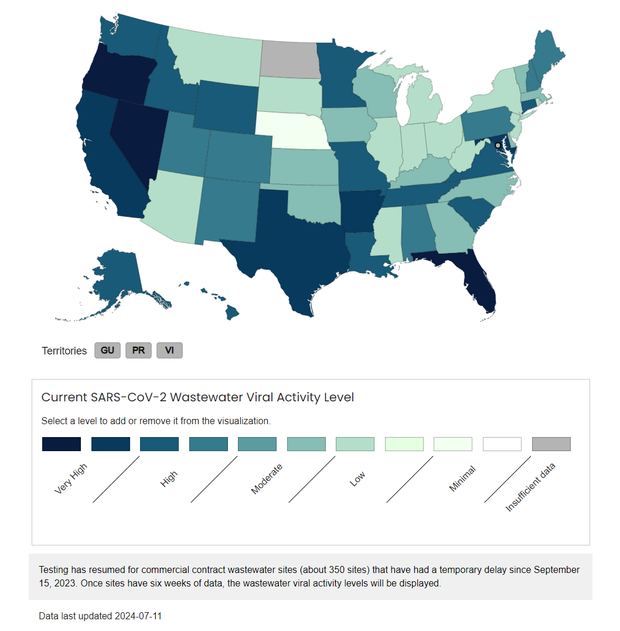

More than half of states are now testing wastewater for “high” or “very high” levels of SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, according to figures released Friday by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Corona Wave This Summer The country’s share is growing.

Nationally, the CDC said overall levels of SARS-CoV-2 in wastewater are “high” for the first time since last winter. In Western states, levels remain “high,” the trend is changing for the first time. It started to get worse Other areas also saw steeper increases at or near “high” levels last month.

The Friday update will be the first since last month due to the July 4th holiday.

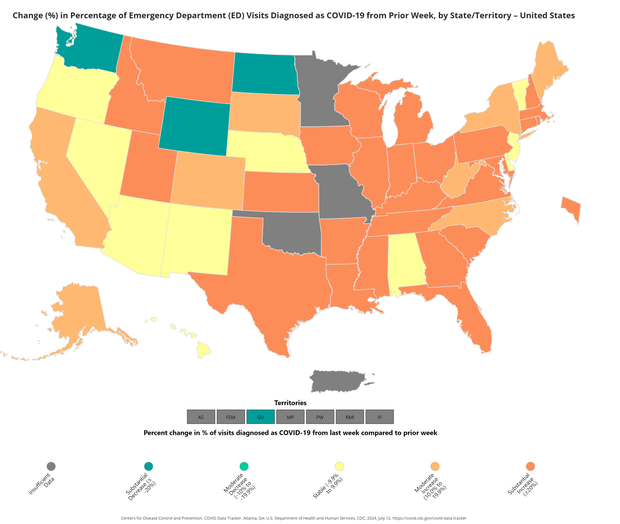

The increase coincides with an increase in the number of COVID-19 patients presenting to emergency rooms. The agency says the District of Columbia and 26 states are currently seeing a “significant increase” in COVID-19 emergency room visits.

The average percentage of COVID-19 patients admitted to emergency rooms nationwide also hit its highest level since February, up 115% from a month earlier.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Overall trends in emergency room visits and hospitalizations remain at levels the CDC considers “low” in several states, well below the deadly peaks reached early in the pandemic.

But COVID-19 emergency room visits have topped “moderate” levels since Hawaii experienced a surge last month that surpassed the virus’s last two waves. Florida has also now reached “moderate” levels. It’s at the peak I haven’t seen it since last winter.

“We’re seeing a pattern that’s consistent with what we’ve seen over the past few summers, except that the increase in activity this time of year is not as dramatic as what we see during the winter peak,” said Aaron Hall, deputy science director for CDC’s coronavirus and other respiratory viruses division.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Health authorities Some communities The rising trend in recent weeks is a signal that it is now time for Americans who want to avoid getting COVID-19, especially those with underlying health problems, to start getting extra doses. Precautions such as wearing a mask And we conducted tests in several regions across the country.

Hall said the recent surge doesn’t appear to be more severe than last summer’s surge, but it’s a reminder that it’s important for people at high risk for severe illness to get vaccinated and take other steps, including seeking medical care.

“The activity we’re seeing now is consistent with previous trends. It’s not necessarily something that should cause additional alarm, but it’s an important reminder that there are key steps people can take to protect themselves,” he said.

When will COVID-19 peak this summer?

Most of the states were among the first to reach “high” levels of COVID-19 in wastewater last month From the westThe proportion of COVID-19 patients in emergency rooms has also skyrocketed. The area has also seen an increase in reported infections in nursing homes.

Other countries have also seen their COVID-19 trends pick up earlier this summer than last year, with COVID-19 hospitalizations in the UK at levels not seen since February.

But there are signs that the summer wave may now be peaking in some states across the region, where the virus first gained traction.

According to forecasts updated by the CDC this week, COVID-19 infections are increasing in nearly every state, but are estimated to be “stable or uncertain” in three states: Hawaii, Oregon and New Mexico.

“It’s hard to predict the future, and if COVID has taught us anything, it’s that things can always change. But based on previous trends, we can expect a summer wave this year that peaks around July or August,” Hall said.

Nursing home infections in the Pacific Northwest, which stretches from Alaska to Oregon, have declined for a second straight week.

This summer, Hawaii saw its emergency room cases of COVID-19 peak at levels worse than the virus outbreak last winter and summer, before cases there began to slow for several weeks.

Hall warned that while COVID-19 trends have slowed since their summer peaks in recent years, they are still far more severe than the low levels seen during past spring virus lulls.

“At least historically, there isn’t necessarily a low or a bottom between the summer and winter waves, and that’s important when you think about protecting vulnerable people,” he said.

What are the latest variants of COVID-19 spreading?

The CDC last updated its variant forecasts every two weeks since July 4, and estimated: KP.3 The variant virus has grown to account for more than a third of infections nationwide.

After that KP.2 and LB.1 Two close relatives of the JN.1 strain, the variants that dominated infections last winter, combined accounted for more than three out of every four infections nationwide.

Hall said there is “no indication yet of increased severity of illness” associated with these variants, similar to what the agency has said in recent weeks.

Hall said the agency is tracking data from hospitals and ongoing studies, as well as detailed analyses of genetic changes in the virus, looking for signs that new variants may pose an increased risk.

“No data source suggests that this variant causes more severe disease than what we’ve seen before,” he said.

As of late June, the CDC estimated that there was a mix of variants present in every region across the country, but that some regions may have had more variants present than others.

KP.3 accounts for the lion’s share of infections in many parts of the United States, while LB.1 is larger in New York and New Jersey and KP.2 is larger in New England.

While KP.3 and LB.1 are currently the fastest-spreading variants, their relative growth rates appear to be “significantly lower” than previous, highly mutated strains, such as the original Omicron variant, Hall said.

“It’s not as dramatic as some of the changes we’ve seen in the virus before,” he said.