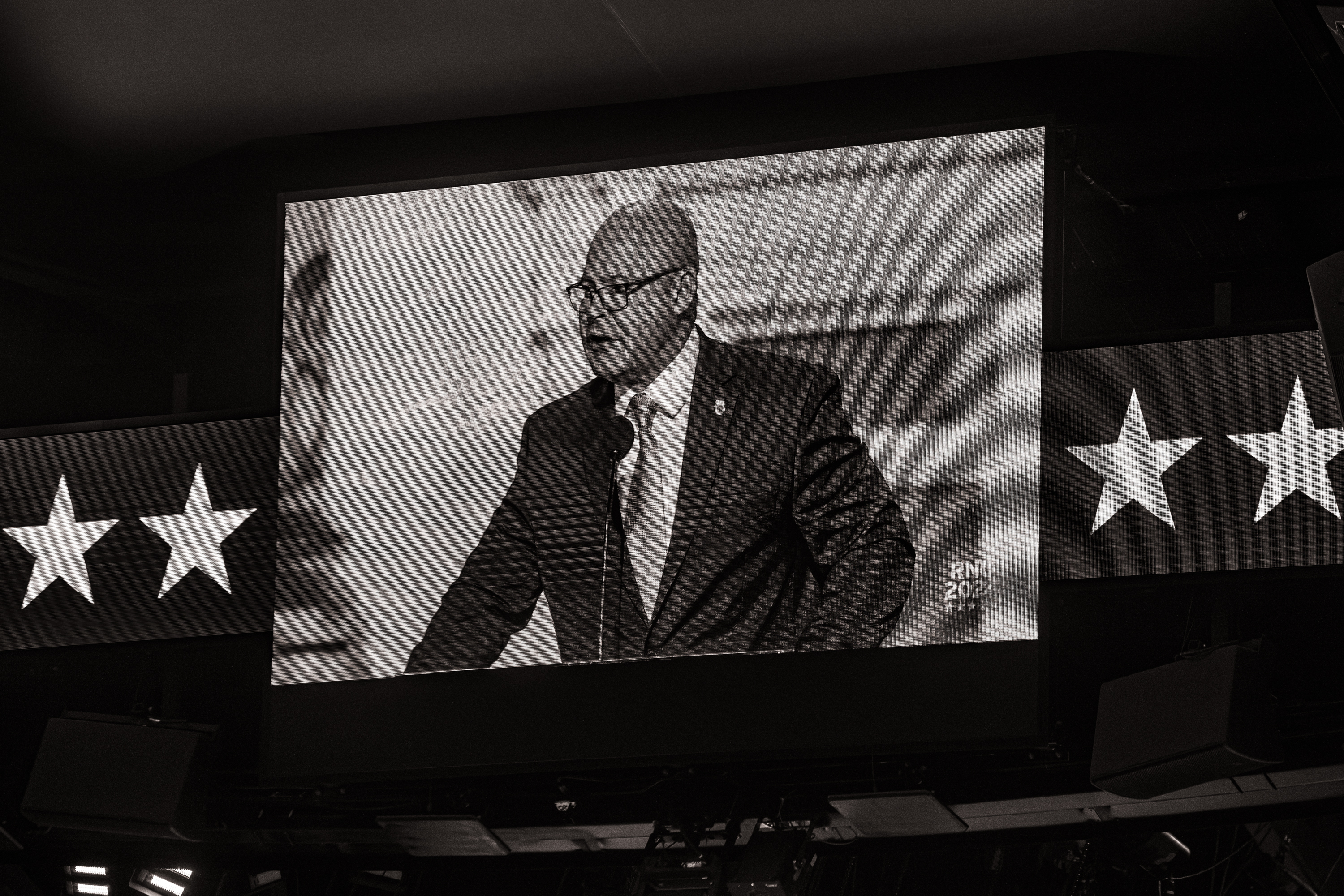

On the first night of the Republican National Convention, I settled into a seat in the upper levels of Milwaukee’s Fiserv Forum to watch the most incongruous political address of my life. The speaker was Sean O’Brien, the general president of the International Brotherhood of Teamsters. The subject was the betrayal of the American worker. The audience included many of the kinds of people he held responsible for that treachery.

O’Brien, whose union has not endorsed Donald Trump, started off nice but soon got angry. He slammed the “economic terrorism” of corporations firing employees who try to organize and attacked business groups like the US Chamber of Commerce. As he worked further into his list of grievances, the applause grew more and more tepid, until it finally just seemed to stop. Trump and his newly announced running mate, Sen. J.D. Vance of Ohio—whom O’Brien singled out for praise for having recently walked a picket line—stood politely throughout. Occasionally, the former president turned to his would-be vice president, cracked a joke, and smiled.

If you suspended your skepticism for a moment, it looked like a glimpse of the anti-corporate, anti-elite Republican Party that Vance, a self-styled spokesman of “forgotten” people, has promised to usher in. Then I checked my notifications and found the Republican Party that Vance more concretely represents. Around the same time O’Brien took the stage, another figure who has historically shied away from events like the RNC was shaking up the race in his own unprecedented way: The Wall Street Journal reported that one of the world’s richest union-busters, Elon Musk, was planning to donate $45 million a month to a super-PAC supporting the Republican campaign.

The Republican convention was defined by the basic tension between the image Trump sought to project and the purpose his candidacy ultimately serves. In many ways, some cosmetic and others not, it was a far different event than any Republican convention in memory. The gathering offered a glimpse of a potentially unbeatable electoral coalition this November—a unified MAGA movement that’s making inroads with Black men, Latino voters, Gen Z, and union members. Republicans were expanding the tent by granting admittance to anyone who shared their antipathy to migrants, pronouns, and $5 gas. Vance, a Never Trumper–turned–MAGA heir, was a symbol of that vibe shift, promising an ideological realignment built to last. But his star turn in Milwaukee suggested a different story, one that might sound less like O’Brien and more like Musk. It was not the rise of the workers. It was the restoration of the bosses.

I spent much of the day after O’Brien’s speech talking to Republicans about his remarks. Everyone was in favor of the union leader speaking (though Wisconsin Sen. Ron Johnson, in an extremely Ron Johnson moment, told me that he hadn’t seen it). But it wasn’t so much due to the content of the speech. O’Brien’s appearance was an example, Trump supporters told me, of the sort of deal-making and coalition-building they believed only he could swing. It would “shred the Democrats,” as one Nebraska Republican put it.

Indeed, the whole convention sometimes seemed like a demonstration of Trump’s power of persuasion. From the model and rapper Amber Rose to Linda Fornos, a Nicaraguan immigrant who sells life insurance in Las Vegas, and San Francisco investor David Sacks, the refrain was the same: They never thought they’d find themselves agreeing with Trump—until Trump won them over. Come to think of it, that is also the story of Vance.

Some of the people I talked to were supportive of a more pro-labor GOP. Barbara Porcella, a Republican from Long Island in New York who comes from a family of union plumbers, told me O’Brien “nailed it, he absolutely nailed it.” Perhaps not coincidentally, New York is one of the states where Trump has made the biggest inroads in recent years. A Politico story on the state’s drift reported that union leaders were “alarmed” by Trump’s strength among their members.

“I don’t know why the unions vote Democrat,” Porcella said.

But the answers to that question were toting red lanyards just like hers. Every time I went to the convention floor from the media filing area later that night, I took an escalator past the Uline Lounge, a VIP area named for the Wisconsin-based packaging moguls who have poured vast amounts of money into combating union power. Sitting behind Trump in the presidential box one night was South Carolina Gov. Henry McMaster, who in January, in the midst of a yearslong battle with the International Longshoremen’s Association, pledged to fight the union “all the way to the gates of hell.” Not far away, foot traffic came to a standstill as people lined up to take a photo or have a word with Markwayne Mullin, the senator from Oklahoma who nearly fought O’Brien at a hearing. Also in the building was Tate Reeves, the Mississippi governor who signed a joint statement with McMaster and four other governors in April declaring that the United Auto Workers’ organizing efforts in the South “threaten our jobs and the values we live by.” (Disclosure: I and most Mother Jones employees are members of the UAW.)

One of the week’s memorable visuals was West Virginia Gov. Jim Justice, the party’s nominee to replace Joe Manchin in the Senate, appearing on stage alongside his bulldog, Babydog, who sat on a little chair. Babydog was pretty cute. Justice’s record isn’t. Retired coal miners have sued the party-switching billionaire resort owner repeatedly to force his companies to pay the health benefits they promised. Everywhere you turned there was someone for whom unions were not a vital new constituency in a workers’ party, but a speed bump on the road to higher profits.

“We’ve become the party of the working men and women in this country; Democrats are the party of wokeness,” Johnson told me, after saying he’d look up O’Brien’s speech on YouTube “if it’s a good one.” There was room, he added, to “talk to, particularly, private-sector unions.”

But Johnson has never offered much support for private-sector unions, nor has he backed the sort of workers whom Vance would later, in his own speech, blame Democrats for selling out. Johnson was one of the party’s loudest proponents of offshoring American manufacturing jobs. He once told a group of Realtors: “Let the billions of people around the world…provide us these goods—high-quality, dirt-cheap.”

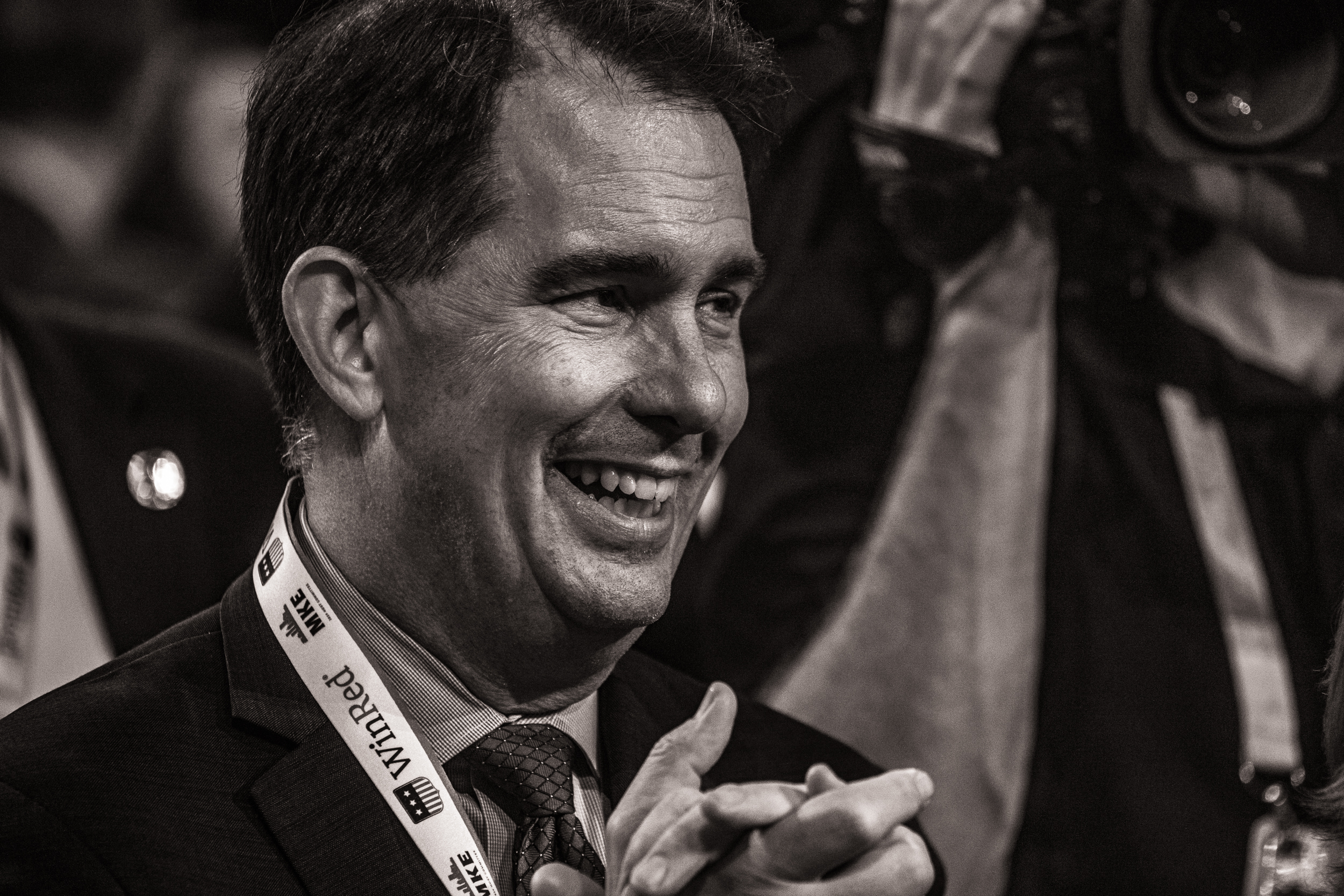

Outside the arena Tuesday, I found Scott Walker, the former Wisconsin governor whose 2011 law gutted the ability of public-sector unions to collectively bargain. (A recent state court ruling struck down much of that law.) Walker’s union-busting push defined a whole era of conservative governance. He was the fulfillment of a dream—a million white papers and donor retreats crawled so that one day he might walk.

“(I’m) glad that he was there, glad that he seems to be supporting the president,” he said of O’Brien. “I don’t always have to agree with every speaker on everything, but I was happy he was there, just as I was happy to have union”—he paused to choose his words carefully—“private-sector union support when I was running for governor.”

I asked the state’s most famous union-buster if Republicans should take the Teamster’s advice and become more pro-union. He offered a substitution.

“I think they’re pro-worker,” he said. “That’s the key.”

After O’Brien left town, with a good deal of his membership criticizing him for the stunt, the party’s public flirtation with organized labor seemed to fade away for a while. No one in this new workers’ party mentioned unions again Tuesday night or for most of the program Wednesday. The Teamsters were like any number of people and issues in Trump’s orbit: The value was in having his name attached to theirs; the rest was diminishing returns.

It fell to Vance, on Wednesday, to pick up the subject and mold it into something more palatable to the audience. “We need a leader who fights for the people who built this country,” he told the audience, and who “answers to the working man, union and non-union alike.” Vance spoke those words deliberately, as if there was something profound about his having said it out loud—the way a politician might have once declared their support for same-sex marriage.

Vance’s speech was, like O’Brien’s, the kind of thing you never would have heard at the Republican convention in years past. Weaving in stories from his bestselling memoir, he sketched a picture of Middletown, Ohio, as a place that Democrats and Republicans gutted with destructive trade deals and disastrous foreign policy. “Jobs were sent overseas and our children were sent to war,” he said. Vance was well-positioned to make that case. He is a famously good storyteller whose life story is so compelling that, as his wife, Usha, pointed out moments before, it has already been the subject of a Ron Howard film.

But Vance was chosen not just because of the people he once knew back home, but because of the people on his Venmo now. Take that big incoming donation from Musk. The Tesla founder had reportedly spent the last few weeks lobbying Trump to choose Vance as his running mate. So had billionaire Palantir founder Peter Thiel, with whom Musk and Vance had both worked. As my colleague Jacob Rosenberg wrote this week, Vance may have started as a rural-white whisperer for liberal elites, but he rose to power in the MAGA universe through his ability to explain Trumpism to conservative and libertarian Silicon Valley elites.

The burgeoning anti-monopolist wing of the GOP is a real thing. Some elected officials, including a few whom O’Brien had praised by name, have shown more of a willingness to publicly align themselves with certain unions. But the people who phoned Trump to lobby for Vance are not clamoring for passage of the PRO Act. They did not call in their chits to get Republican senators to vote to shore up Teamster pensions. They aren’t advocating for a living wage for restaurant workers. They are the people O’Brien was purportedly there to tear down. Thiel is a monopolist. Musk wants to make trucking autonomous. The Tesla boss, who is now one of the biggest political donors in history, has threatened to take away stock options from unionizing employees at Tesla and is currently suing to eliminate the National Labor Relations Board. For these people, the appeal of Vance is not any gesture to the UAW, but a kind of sweeping, techno-authoritarian transformation. They are not anti-elite. They are the elite.

You don’t have to speculate about how Trump would deal with unions as president, because he has been president before. During his first term, Trump’s NLRB appointees were notoriously anti-union, and corporate interests such as Musk are banking on his army of conservative appointees to the federal bench gutting labor protections even further. That’s in stark contrast to the man Trump is running against, whom the New Yorker called “the most pro-labor president since FDR,” largely thanks to the aggressive intervention of his NLRB.

On Wednesday, as Vance offered his toned-down style of class war, Trump offered more signs that a second term would continue to favor the c-suite in a lengthy interview with Bloomberg. He was proposing nearly $1 trillion in corporate tax cuts and floating JPMorgan Chase CEO Jamie Dimon as his future Treasury secretary. Trump had already promised oil company executives that he would put the brakes on electric-vehicle incentives while asking for $1 billion in campaign cash.

Trump, in a rambling acceptance speech Thursday, reiterated that promise while rebranding it as a deal for workers. He would scrap the new electric-car incentives on day one, he said, and impose a massive tariff on Chinese vehicles made in Mexico. (Biden has already imposed one.) Then he singled out the UAW’s president, Shawn Fain, who in the last year had secured a new contract with the Big Three after a historic strike and presided over the first successful union drive at a Southern automobile plant.

“The United Auto Workers ought to be ashamed for allowing this to happen,” Trump said of the Chinese vehicles, “and the leader of the United Auto Workers should be fired immediately, and every autoworker—union and non-union—should be voting for Donald Trump.”

It was a fitting end to the Republican rebrand that wasn’t—a billionaire boss, whose catchphrase is “You’re fired,” reaching out to the workers of the world by demanding their leader be laid off.

It wasn’t just the pro-worker facade. The convention was different in other ways, too. The assassination attempt added a shock of religious fervor to a cause that had never been lacking in it. Tucker Carlson called Trump’s survival “divine intervention.” On my first day in town, I met a woman who had been standing right behind Trump when the ex-president was shot, then drove more than 500 miles just to see him again. It was just a thing she had to do. A Florida woman who had stood behind Trump at a different rally just a few days before that told me that taking a bullet for the ex-president would have been the great honor of her life.

“I’d be pleased. I’d be happy,” she said. “And my mom says the same thing.”

People stopped posing for photos with the Trumpian thumbs-up and started raising their fists instead. On my way to the security checkpoint, a guy dressed as Uncle Sam wheeled up to me on an electric scooter and turned to show me the white patch on his ear. You saw more and more of those little white squares over the course of the week. The whole thing was a sign from God, supporters said, and to be fair, spiritual awakenings have often stemmed from less. Musk himself had been caught up in the moment, confessing his loyalty to Trump on a dashed-off X post minutes after the shooting, as if he had suddenly gazed into the fiery furnace and seen the truth.

The party had never seemed so unified, even if the reason for that unity was that everyone who might otherwise have spoken out had stayed home or been cast aside. Vance was there because some of the people in this same movement had wanted to hang former Vice President Mike Pence. (That Pence had survived was not generally considered an act of providence.) Sitting in Milwaukee, seeing a party that was so much more put together than it was when it last won in 2016, and so much more deliberate in its outreach, it was hard to shake the impression that this might all actually work. The Democrats were something more than a mess. The polls were all coming up Trump.

It is a powerful coalition, but it is not a particularly well-balanced one. Some people are going to cash in, and some people are going to get screwed. The bad news for O’Brien, and the good news for Musk, is that it’s usually the people who spend $200 million who leave the auction with what they paid for.