Connie Chung’s career began with a position. “I walked into a local TV station and said, ‘I can learn. I don’t have any experience, but I can do this. ‘ … You know when you’re young and you don’t know any better? I just went ahead and acted like I knew what I was doing.”

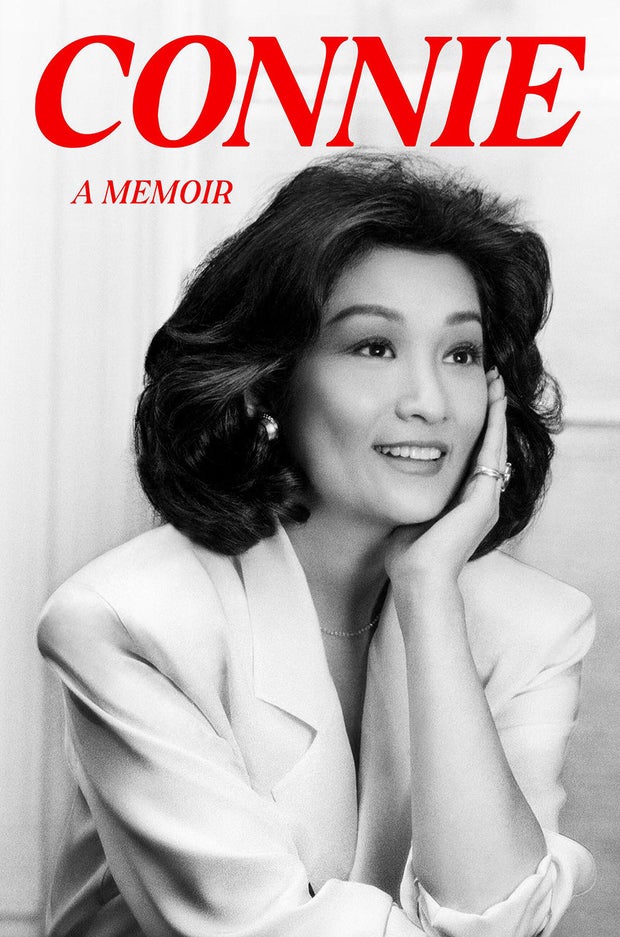

And as she writes in her new memoir, “Connie” (out Tuesday), no one could possibly do more for Connie’s information.

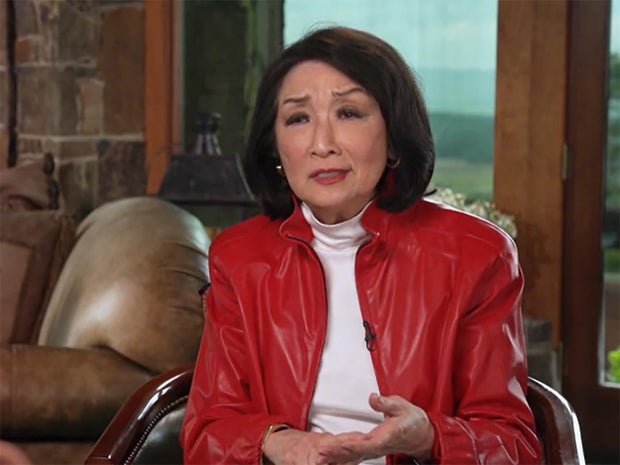

She looks back on her 40-year career from her home in Montana, taking in the scenery with her husband of nearly 40 years, daytime TV legend Maury Povich.

Grand Central Publishing

“She wanted a job, and the news director said, ‘No, no, no, you’re my secretary,’” recalls Povich, then a rising star in the newsroom. “She said, ‘No, I want that job, weekend writer on the news desk.’ And he said, ‘Well, you’ve got to replace yourself.’ She left the newsroom, went across the street to the bank, looked at the first female teller, and said, Do you want to be on TV? “I took her across the street to the newsroom. She got a job, and the banker got a job as a secretary.”

Soon she caught the eye of CBS News, who, with a cameraman, stormed into the restaurant accused of health violations. “Look, there was the CBS bureau chief sitting down to lunch,” Cheung said. “He looked at me and gave me his business card and said, Call me” .

In 1971, in what she described as a “sea of men” at the CBS News Washington bureau, Cheung devised a survival plan. “I looked around and said, ‘Well, I’m going to be a man.’ So I took on their characteristics. I had courage and I walked into the room like I owned it!”

And she could say, like a sailor, “I had this dirty reputation of saying unexpected things to these men, which were somewhat sexist and racist. And they were like, and! But bad words? Not good. I wouldn’t recommend it to anyone. It’s just my MO on how to survive that snake pit.”

White House photo, courtesy of the Nixon Presidential Library and Museum.

Climbing up one level at a time wasn’t enough for Chung. When NBC wanted to hire someone to do a half-hour newscast before the “Today” show, Chung said, “I’ll do it! But not just any newscast, I want to do Tom Brokaw’s ‘Nightly News’ and do political stories. And I want to do ‘Saturday Night News.’ And I want to do ‘Newsbreaks’ at 9 and 10 p.m. That would be really hard to sleep.”

Polly asked, “You seem to be a strong mix of American and Chinese. American, opportunity, Chinese?”

“It’s mandatory,” said Jeong. “Always do the right thing. He’s a good guy. He’s polite.”

“Ambition? Drive? Focus?”

“Yeah, of course,” Cheung replied. “The will to succeed. It was a combo platter.”

NBC News

The most popular interview in the competitive network competition was The Get. In November 1991, Magic Johnson, the great point guard of the Los Angeles Lakers, revealed that he was HIV positive. “I went to his agent’s office and squatted down. I didn’t leave until he left the office,” Chung said. She got the interview.

She has her first interview with the captain of the Exxon Valdez since the Alaskan oil spill.

Tonya Harding’s skating scandal and provocatively titled documentary (“Life in the Fat Lane”) got good ratings, but the tabloid scrutiny tarnished her name and reputation.

“The story went on and I didn’t have the strength to refuse,” said Mr. Jeong. “And I regret it very much, Jane.”

CBS News

The daughter of “very, very traditional” Chinese immigrants, Connie was the youngest of five sisters and the only one born in the U.S. Her father decided she would be the son he never had, and took the surname Cheung.

She exceeded his expectations and realized her dream, becoming co-anchor of the “CBS Evening News” with Dan Rather in 1993.

But it wasn’t a dream team. She recalled a line from the Bette Davis movie “All About Eve.” “She was walking up the stairs and she said, ‘Fasten your seatbelts, it’s going to be a bumpy night.’ And I thought, Yeah! Wait a minute, honey!”

Two years later, she was fired. She said she was “completely devastated.”

But a few days later, after years of miscarriages and fertility treatments, their adopted son was born. “We brought Matthew in when he was less than a day old,” Cheung said. “He never left my arms. He was an extension of my arms. And to this day, he’s a grown man, and he’s doing really well.”

At the age of 49, Connie Cheng had almost everything, and admitted, “I can never claim to be successful. I was born Chinese. I was born humble. It’s never enough.”

According to Povich, it took “Generation Connie” to realize exactly what kind of person she had become.

Last year, the New York Times ran an article titled “The Connie Generation,” which described Chinese, Korean and Japanese parents across the country naming their daughters after her.

“I couldn’t believe it,” Jeong said. “It was the most exciting day I could ever imagine. They were the ones who declared me a success. And after they did, I thought, Really? You have to accept that.“

Web Addition: Connie Chung Becomes Role Model (YouTube Video)

Polly asked, “What did you mean to those parents?”

“Work hard, be brave, and take risks,” said Jeong. “I wasn’t the smartest. I wasn’t the strongest. But I did those three things.”

Read an excerpt: “Connie: A Memoir” by Connie Cheung

For more information:

Story written by Jay Kernis. Edited by Mike Levine.

See also: