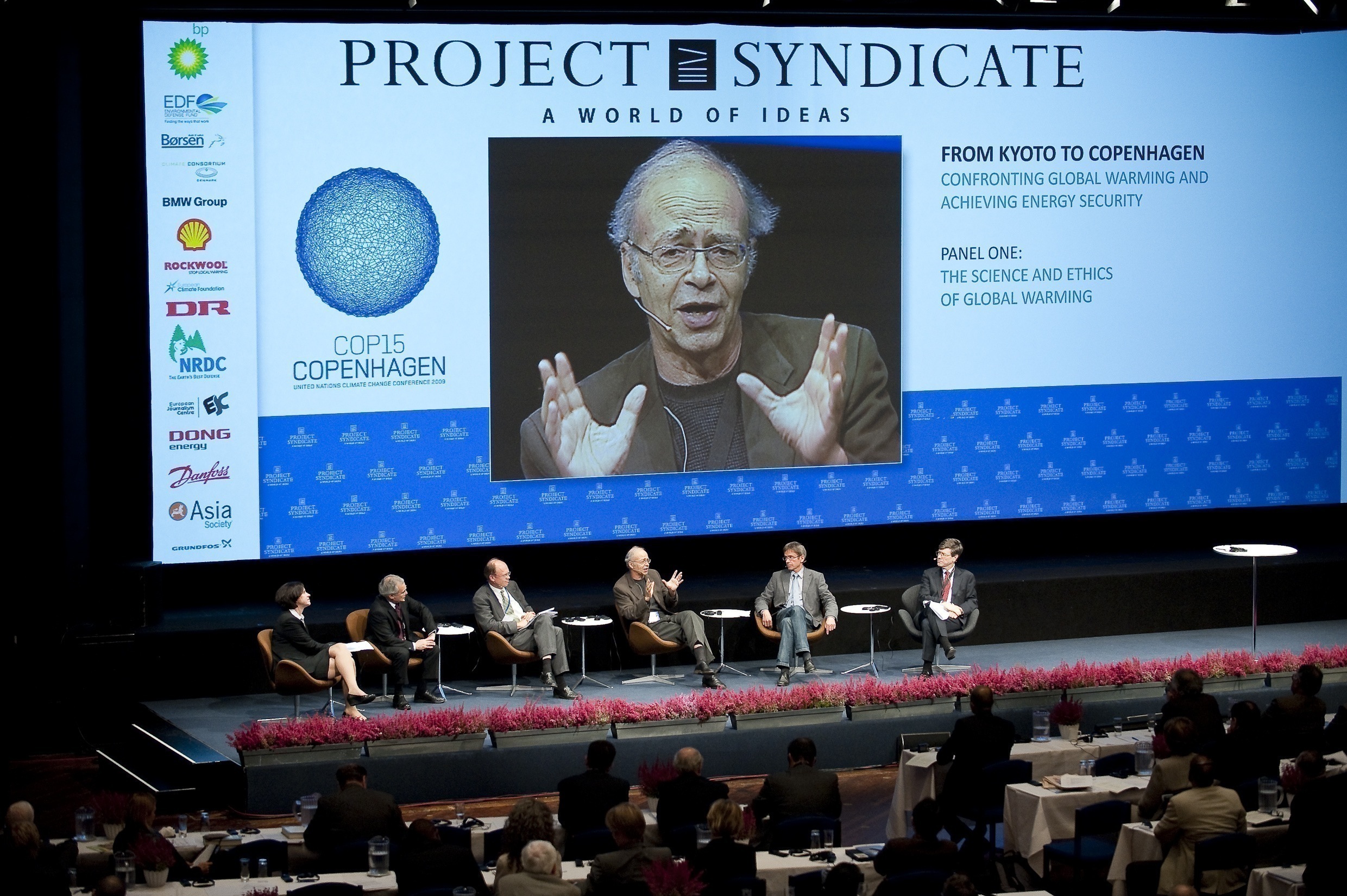

In a Princeton University lecture hall one morning last December, Peter Singer, one of the world’s most influential—and controversial—living philosophers, offered his Philosophy 385 (“Practical Ethics”) students a brief overview of their upcoming final. The registrar, he noted, had scheduled the exam for the following Sunday evening. This, he proclaimed, “seems unethical.”

The line got a good laugh. A hint of winter chill hung in the air, the undergrads having just sloughed off their Canada Goose parkas and settled into the seats of Wood Auditorium in McCosh Hall, a Tudor Gothic behemoth that was once the largest building on campus. It was here, 102 years earlier, that Albert Einstein described his theory of relativity to a packed house.

The 200 students enrolled in Philosophy 385—about as many as in all other Princeton philosophy classes combined—were acutely aware, per the course syllabus, that they were his final crop:

This course will challenge you to examine your life from an ethical perspective. NOTE: This will be the last time I teach this course before my retirement from Princeton University.

In May, following a two-day farewell conference, the now-78-year-old Australian bade farewell to Princeton and, with a perceptible measure of good riddance, the United States, his second home for more than a quarter-century. For his final class, Singer had prepared a PowerPoint looking back on his years at Princeton—and America.

It’s striking to consider the extent to which the United States has been shaped by Singer’s version of utilitarianism—the belief that actions are ethical insomuch as they increase our collective pleasure and limit our collective suffering. His addition to this ancient idea is simple and profound: Singer believes that all pain experienced by sentient beings counts the same.

The logical extensions of his intellectual positions have on occasion caused great controversy, as when Singer’s belief that newborns lack sentience led him to assert that in extreme cases, parents should have the right to end the life of a severely disabled infant. In response, a disability rights organization dubbed him “the most dangerous man on earth.” Generally speaking, Singer sees few ideas as off-limits. He recently helped launch the Journal of Controversial Ideas, which last fall published an article on whether zoophilia is morally permissible.

Whatever one might think of Singer’s ideas, there’s no doubt they’ve had a great deal of impact. Interest-based utilitarianism is at the root of Singer’s path-breaking advocacy for animal rights and, somewhat controversially, of effective altruism, the charitable principle famously espoused by cryptocurrency entrepreneur Sam Bankman-Fried, who was convicted of fraud last year. Earlier this year, along with Polish philosopher Katarzyna de Lazari-Radek, Singer launched a podcast exploring how to live an ethical, meaningful life.

Perhaps most profoundly, his philosophy flicks at the core of America’s democratic project. While the Founding Fathers were most influenced by John Locke, it was John Stuart Mill—a utilitarian—whose ideas shaped the evolution of constitutional liberalism in the second half of the 20th century. As we face one of the most fraught political periods in recent memory, it’s sobering to hear Singer’s take on America’s shortcomings—and his assessment of what’s to come.

Singer first arrived in the US in 1973, shortly after finishing his graduate work at Oxford University. He was accompanied by his wife, Renata, who’d recently given birth to their first child. The couple had planned to return to Australia to raise their daughter but wanted to spend some time in the States first. “Obviously, everything in America is a big presence growing up in Australia,” Singer told me during one of several interviews.

On the advice of philosopher Derek Parfit, another influential philosopher of Singer’s generation, Singer accepted a visiting professorship at New York University and settled into university housing on Bleecker Street in Greenwich Village.

The NYU position came with the possibility of a two-year extension, but the college was then on the verge of bankruptcy. It ultimately sold off its uptown campus, and the administrators informed Singer that they wouldn’t renew his contract. “We were reasonably okay with that,” he recalls. “We didn’t want our children to grow up as Americans, really.” He quickly landed an appointment at La Trobe University in Melbourne, Australia.

“‘Animal Liberation’ lit the fire for me,” says the attorney and activist Cheryl Leahy. “You cannot overstate the importance of Singer’s work in influencing and launching this movement.”

With time to kill between jobs, he spent the fall of 1974 teaching a continuing education course. In it, he presented a draft of a manuscript based on an essay he’d published the year before in the New York Review of Books. The piece was inspired in part by Singer’s decision, four years earlier on Earth Day, to stop eating meat. It was persuasive enough to convince the Review’s founder and editor, Robert Silvers, to become a vegetarian.

Published in 1975 with the same title, Animal Liberation is almost inarguably the most important book in the history of animal rights. It has remained in print for 50 years and been read by almost everyone in the field. Cheryl Leahy read it at age 13, after a classmate accused her in the lunchroom of eating the “decomposing flesh of a tortured animal.”

Today, Leahy is executive director of Animal Outlook, a nonprofit focused on animal protection, and has spent her 20-year career as an attorney advocating for the interests of nonhuman beings. “Animal Liberation lit the fire for me,” she told me. “It probably did for countless people. You cannot overstate the importance of Singer’s work in influencing and launching this movement.”

Thanks in part to Singer, vegetarianism in the United States has increased over the years. In 1994, barely 1 percent of Americans self-identified as vegetarian or vegan. Recent surveys put the rate at 5 to 8 percent. Yet with population growth, the US public now consumes more meat than ever, and the vast majority of factory-farmed animals still live short, miserable lives. Even “cage-free” hens, Singer laments, are generally crowded into giant sheds with thousands of birds. “I’m disappointed (the animal welfare movement) hasn’t gone further,” he told the class I attended.

Some 25 years after the couple’s NYU adventure, Singer received an invitation to teach at Princeton. Their kids were grown, and he and Renata had been contemplating a move anyway. “In fact,” he says, “we’d been talking about going to a Third World country for something quite different.” But a friend, animal rights activist Henry Spira, argued that Singer had a greater obligation: “Henry said to me at some stage, ‘You ought to come over the United States because it’s a much bigger pond and you’ll have a much bigger impact. The United States needs your ideas just as much as Australia, but it’s 15 times bigger and you’ll have more of a world influence.’” The offer proved “just a bit too tempting to turn down.”

Back in the lecture hall, with Australian understatement, Singer informed his students that his 1999 hiring “caused something of a stir.” Indeed, the New York Times ran a front-page article declaring that no academic appointment had caused such controversy since 1940, when City College had tried to hire atheist philosopher Bertrand Russell.

Editorial writers, the story noted, “have compared Mr. Singer’s hiring to that of a Nazi.” Then-Republican presidential candidate Steve Forbes, a Princeton alum and supporter, threatened to stop donating to the university if the appointment stood. Protesters blocked the entrance to Nassau Hall, the administration building, because of Singer’s support of euthanasia in extreme circumstances. But Princeton President Harold Shapiro stood behind Singer, and the hubbub subsided.

Given all of this year’s campus upheaval over Israel’s activities in Gaza, Singer’s hiring kerfuffle seems almost quaint today. I asked several of his students whether their professor had stirred up any serious controversy during the semester—all said no. During the lecture, when Singer spoke proudly of his role in launching the Journal of Controversial Ideas, no one seemed to bat an eye.

Near the end of his lecture, Singer addressed an elephant in the room—Bankman-Fried, the cryptocurrency exchange founder who’d just been convicted of defrauding customers and investors out of at least $10 billion. Bankman-Fried also ranked among the most prominent champions of effective altruism (EA), a movement inspired in significant part by Singer’s 1971 article “Famine, Affluence, and Morality.”

EA proponents generally advocate for using data and reason to maximize the future benefits of any charitable action. In his paper, Singer argued that the failure of wealthy people to contribute to humanitarian causes was akin to failing to help a child drowning in a shallow pond. He was referring in this case to a famine afflicting Bangladeshi war refugees, but the argument applied generally.

In 2009, inspired by Singer’s work, Oxford philosophers Toby Ord and Will MacAskill launched an organization, Giving What We Can, framed around their pledge to donate at least a tenth of their income to effective charities. The next year, Bill Gates and Warren Buffett invited fellow billionaires to take the Giving Pledge, a vow to dedicate the majority of their wealth to charitable causes. When a group of 17 billionaires signed the pledge in late 2010, the press release included a statement from Singer.

Singer explained to his students how Sam Bankman-Fried had claimed he’d never intended to commit fraud and “sometimes life creeps up on you.” He lowered his voice and added, “Well, be warned: Don’t let life creep up on you.”

Although their causes and motivations have been questioned, the notion that rich people ought to be more altruistic—the “A” in EA—is not a matter of serious dispute. It’s the “E” where things get complicated.

In 2013, Singer co-founded The Life You Can Save, an organization named after one of his books that attempts to quantify and maximize charitable impact, often in terms of quality-adjusted life years, a metric borrowed from the public health universe. In practical terms, this usually means steering money to causes that benefit developing nations as opposed to, say, your elementary school PTA.

At the heart of MacAskill’s own 2016 book, Doing Good Better, is the idea that a dollar spent by a citizen of a rich country could do 100 times more good if spent in an impoverished nation. This notion is not particularly controversial either, at least not among ethicists, who by and large would agree that giving to the opera is neither charitable nor effective by any meaningful definition of the words.

But then there’s “longtermism,” an EA offshoot that prioritizes the elimination of existential risks such as biological and nuclear weapons, climate change, and malicious AIs, which longtermers say could wreak havoc on future humans or other forms of life—which could include (non-malicious) sentient AIs. In a more recent book, What We Owe the Future, MacAskill casts protecting the denizens of the distant future as the moral imperative of our time—the ultimate cause.

This view is highly controversial. The New School for Social Research philosophy professor Alice Crary, a prominent critic, calls longtermism “toxic” because of the stark utilitarian tradeoff it embraces. The focus on “existential risk,” she writes, “marks a dramatic shift from the concern with present and near-term suffering that is the hallmark of their effective altruist progenitors.”

Effective altruism, which Singer’s work helped inspire, “makes students in places like Princeton feel like they’re the heroic rescuers of the world,” says philosopher Alice Crary. “And these institutions have enriched themselves off of it.”

Singer distances himself from strong longtermism in part for this reason. He’s also skeptical of the longtermers’ more speculative projects, like aiming to protect the interests of sentient nonhumans. Utilitarians, Singer says, are split on whether hypothetical beings deserve the same consideration as actual humans. “That I still regard as one of the most difficult and baffling issues in ethical theory,” he says.

He’s also doubtful that we can meaningfully adjust our actions to do good in the distant future and is thus careful to distinguish between the dangers from asteroids and viruses—“where we can significantly reduce risks for modest amounts of money”—and more abstract projects. As for general artificial intelligence, AI that broadly matches or surpasses human capabilities, “we don’t know whether that will come, we don’t when it is coming, and we don’t really know what we could do now that would reduce that risk.”

But Singer is more tolerant of the notion of pursuing a high income with the intent to donate a sizable portion to charity. The EA community calls this “earning to give,” and it’s a significant part of the work of effective altruist Benjamin Todd’s organization 80,000 Hours (the average person’s work longevity); its disciples included Bankman-Fried, who claimed he aspired to accumulate near-infinite wealth so he could redistribute it.

For his students, Singer put up a slide reading, “Do Good But Don’t Be Sketchy!” explaining how Bankman-Fried had told journalist Kelsey Piper he’d never intended to commit fraud, and “sometimes life creeps up on you.” A father of three and grandfather of four, Singer then lowered his voice. “Well, be warned,” he said. “Don’t let life creep up on you.”

But Singer’s admonition begs the question of whether EA can be used to justify unethical behavior. It certainly seem to rationalize the existence and inform the ethos of elite colleges like Princeton, an institution that admits more students from the top 1 percent of the income distribution than from the bottom 60 percent, and where graduates’ most common career path is “business.”

EA arguably relieves such institutions of the pressure to embrace a more socioeconomically diverse group of students and encourage them toward public-interest careers. “EA makes students in places like Princeton feel like they’re the heroic rescuers of the world,” Crary says. “And these institutions have enriched themselves off of it.”

“Australia does elections better than America. We have ranked-choice voting and we have proportional representation for the Senate. We vote on Saturdays…We have an independent electoral commission, which draws up electoral boundaries.”

Singer might not go that far, but he was willing to sign on as an unpaid adviser (in name only) to Class Action, a nonprofit I co-founded that advocates against inequitable admissions policies at so-called elite colleges and the funneling of graduates into investment banking and management consulting careers.

To his students, Singer said: “You will get asked to donate to various charities after you graduate, and one of them might be to improve education here at Princeton. The question can be raised: Is this the most effective thing that you can do with your donations?”

He acknowledged that they might feel a debt to their alma mater: “But I think you should think of your charitable donations like that in a different pocket from donations where you want to really do the most good in the world.”

While Singer is best known for his influence on animal rights and effective altruism, his Oxford graduate thesis, later published as his first book, focused on the ethics of civil disobedience in democracies. In it, he argues that our voluntary participation in a democratic process obligates us to accept its outcome.

“After the election,” Singer wrote in 1973—amid the Watergate scandal that would lead to then-President Richard Nixon’s resignation—“it is too late to say that one never accepted its validity.” It’s thus only natural that he has followed American politics closely, and critically, ever since the Supreme Court declared George W. Bush president in 2000, shortly after Singer arrived at Princeton. Now, like much of America, he’s anxious about November.

“One of the things that’s absurd about American politics is first-past-the-post voting,” Singer says, citing the practice of allowing voters to select only one candidate and awarding the seat to whomever has the most votes—as opposed to alternative voting systems that are used around the world and widely perceived as fairer. “The reason that Bush was president instead of (Al) Gore was Ralph Nader running for the Greens,” he says. “That was terrible of him, and I’ve never forgiven him, but it also shows how stupid this voting system is. (Donald) Trump never would have gotten the nomination in 2016 if they’d used ranked-choice voting.”

“Australia does elections better than America,” he adds, citing a litany of practices he views as beneficial. “We have ranked-choice voting and we have proportional representation for the Senate. We vote on Saturdays, not a weekday. We have an independent electoral commission, which draws up electoral boundaries—we don’t have politicians do it. We don’t have primaries. We have parliamentary parties elect their leaders, which means they’ve been through the scrutiny of their colleagues, so it’s a much better proving ground for who’s going to be a good leader.”

He holds special enmity for the Electoral College. “Hillary (Clinton) got nearly 3 million more votes than Trump, so she should have been president,” Singer says. “And the gerrymandered electorates are disgraceful as well.”

Singer points to the “great pity” of Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s decision not to retire when she could: “Does Joe Biden really want his legacy to be the reelection of Donald Trump and everything that that will mean?”

Whatever his debt to the United States and its institutions, Singer’s national allegiance is clear. “I’ve never thought of myself as an American,” he says, as we talk about how difficult it is for his countrymen to accept the insanity of US politics. “They are astounded about the gun laws,” he says. “Australia has very tough gun laws, and they were brought in by a conservative prime minister, John Howard. It’s just incredible to me that America cannot see how obviously terrible it is to have guns available to everybody.”

The critiques continue. “America lacks universal health care coverage, which is something that we Australians all take for granted,” Singer says. “This is perhaps more controversial, but we generally don’t think that it’s a good idea to have a Supreme Court that decides issues like abortion.”

Australians, he adds, have difficulty grappling with the outsize sway of money over politics and policy here. “It’s not that money has no influence in Australia,” he explains, “but it doesn’t have the same kind of influence on individual elected representatives, because what matters is the political party—and individual candidates for Parliament don’t have to raise their own money.”

Prior to Trump’s recent criminal conviction, over a vegan lunch at a Princeton dining hall, I ask Singer what he sees in America’s future. “You think philosophers have crystal balls, do you?” he asks with a smile. I counter that I do not, but that readers would be keenly interested in an astute traveler’s observations of our embattled democratic order. “You’re Alexis de Tocqueville in this story,” I say.

“I hope I can live up to it.”

He thinks for a moment. “I don’t know,” he says, finally. “Until recently, I thought that Trump was not going to be electable. I thought he had this 40 percent of hardcore supporters, but that wasn’t going to be enough. But obviously, the polls that have come out recently have been more scary than that. I wish there were a strong Democrat running for office who is not in his 80s, but that doesn’t seem like it’s going to happen.”

Trump’s behavior has polarized the nation and “encouraged this idea that we have our own set of facts,” he emphasizes. “Bush did some of that, too. I think Karl Rove said something like, ‘You’re living in the reality world.’ But Trump has made it so much worse, talking about the fake news stuff just to get people to believe that there were no facts you can agree on. I think that’s been very damaging to democracy.” (Rove has denied that he was the source of the quote in question, which the New York Times Magazine attributed to an anonymous “senior adviser to Bush.”)

Trump would not “do what needs to be done” on climate, and that problem “dwarfs the others,” Singer says. “Another four years, then it’s almost past the time where we can prevent catastrophic climate change.”

Most utilitarians believe that engaging with ideas—even patently false ones—generally serves the greater good, but on the eve of the first presidential debate, which was disastrous for President Joe Biden, Singer said he thought Trump might be the rare exception. Debating Trump, he told me in an email, “would be unethical if this would-be despot, crazy person were not the overwhelmingly likely nominee of one of America’s two major political parties.”

Yet based purely on a political-utilitarian calculus, he figures Biden didn’t have much choice. “I think it would look weak to refuse to debate him,” Singer said. “Trump would make a lot of hay with that. He would say, ‘He’s old and senile and can’t do it.’”

After the debate, Singer wrote on X that “Biden should announce that at the Democratic Convention he will release his delegates to vote for the candidate with the best chance of defeating Trump.” In a follow-up email, he cited the “terrible blot” of Nader’s 2000 presidential campaign on Nader’s own career as a consumer advocate and the “great pity” of Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s decision not to retire from the Supreme Court while Democrats controlled the Senate, which resulted in the reversal of Roe v. Wade “and now is denying the EPA the power to issue essential environmental regulations.”

“Does Joe Biden really want his legacy to be the reelection of Donald Trump and everything that that will mean for the US and the world?” he said.

He fears what a second Trump term might portend. He’s particularly worried about Trump’s fossil-fuel cheerleading and hostility toward climate action. “He’s not going to do what needs to be done, and that’s a huge problem that dwarfs the others. Another four years,” Singer told me, “then it’s almost past the time where we can prevent catastrophic climate change.”

The demise of the founders’ grand experiment isn’t far behind on his worry list: “Would it be the end of American democracy? Probably not is my guess, but there’s a much greater chance of it being the end of American democracy if Trump is elected than if he’s defeated. I wouldn’t like to take that risk. And the fact that he would not support Ukraine against his friend (Russian President Vladimir) Putin, whom he understands so well, is also a big worry. Because that’s not just about the plight of Ukraine, it’s about the rule of law in international affairs.”

His concern extends to the Gaza situation. “Trump is such a loose cannon” that he’s difficult to predict, Singer says. “But given the idea that he’s all about putting America’s interests first and he doesn’t seem to show that he cares much about other people, he may well believe that it’s in America’s interest for the Netanyahu government to do as it wishes. And that may be much worse for the Palestinian people than if Biden, who is at least trying to put some pressure on the Netanyahu government to have a ceasefire, remains in office.”

Back in McCosh Hall, the hour drew to a close—and with it Singer’s Princeton career.

After nearly a quarter-century, there was a palpable sense he’d had enough. His farewell slide to his last-ever Practical Ethics class—which was followed by a rousing standing ovation from the students—had nothing whatsoever to do with philosophy or politics or even ethics.

It was a photo of Singer in a wetsuit, surfboard in hand, practicing a hobby he took up in his 50s. “Bye,” it said. “I’ve gone surfing.”